[1/6] Ultimate Guide: Model for Identifying and Changing Behavior - ABCD Framework Introduction

How to identify the right area of behavior? What is the ABCD Framework and how can I use it? What will this study focus on? I will answer these questions and much more in this article.

This case study will be divided into a series of six articles. I wrote the first article on this topic at the end of 2019, and it has been on my mind ever since. I knew there was potential for something bigger than just four pages. It stayed in my head for several years, and this year I finally decided to dive into it.

It took me several months to put it all together, and it has been one of the most challenging things I’ve written or worked on overall. I will continue to refine the study based on your feedback or new examples. I hope you enjoy it.

For those who would like to support this effort, you can find the entire study here for a symbolic price. It also includes examples and exercises that you won’t find in the article.

Thank you, and I look forward to reading your thoughts.

This is what a practical framework (or model) for identifying, understanding, and modeling behavior looks like. Developed by iNudgeyou, one of the top behavioral companies in the world, it’s used by government organizations like the World Bank, OECD, and the European Union in the creation of new laws.

I’ve brought it to you and transformed it into a practical form that you can use daily in your work. That is the main goal of these articles. There are very few resources on the market that are so practical and filled with examples from behavioral economics.

For over a decade, I’ve had a deep interest in behavioral insights. I use them in everything I do, whether it’s consulting on deals worth hundreds of millions, advising the world’s biggest e-commerce brands like Desigual, working on small online stores, building global products, in ambitious startups, or hedge funds – my interests have evolved over the years. Nevertheless, I’ve been able to excel in these different fields, in some of the best companies and teams, thanks primarily to these insights.

When you try to identify someone’s way of thinking, it’s similar to a doctor trying to figure out what’s wrong with a patient by observing their symptoms and running tests.

People studying behavior use a similar method. They try to understand why someone behaves a certain way by observing clues and evidence. This kind of thinking is called “abductive” reasoning, which means looking for the best possible explanation despite uncertainty.

But let’s go step by step.

In this comprehensive case study, we will focus on understanding human behavior and subconscious decision-making, how to correctly classify it into specific areas, and then, using practical real-life examples, we will demonstrate how to address it in today’s technological world with the best possible effect.

We’ll start by focusing on examples from specific areas, such as creating communication/marketing campaigns or various product initiatives, because it’s easiest to illustrate here. However, the insights from this study can be applied in almost any field where your work directly influences or relates to human behavior and decision-making.

Take a moment to reflect.

Behavior change communication campaigns—like campaigns against texting while driving, quitting smoking, or reminding people not to leave their child in the car—usually don’t work. They tend to serve more as nice PR for companies and good business for agencies.

The same goes for apps that promise to build new habits, like learning a new language, losing weight, or improving productivity.

Despite the massive growth, persistence rates of online courses are significantly low (Xavier and Meneses, 2020) compared to those offered in person (Muljana and Luo, 2019; Delnoij et al., 2020). Online learners struggle to complete their courses (Friðriksdóttir, 2018) and attrition (or termination) is the leading problem encountered in many colleges (Bowden, 2008), which is a foremost challenge for online education administrators/instructors (Clay et al., 2008). The issue is still very challenging (Chiyaka et al., 2016; Hobson and Puruhito, 2018; Johnson et al., 2019; Li and Wong, 2019). Only about 15% of Open Universities students leave with degrees or other qualifications, indicating a meager persistence rate among students taking online courses (Mishra, 2017). Online dropout experience results in frustration and shatters learners’ confidence preventing future enrolments (Poellhuber et al., 2008), which implies inadequacy, questionable quality, and profit loss for institutions (Willging and Johnson, 2009; Gomez, 2013).

Source: Frontiers

Studies show that even though online class enrollment is growing, up to 40–80% of online students drop out!

It’s the same with almost all apps, whether for learning languages, fitness, trading, etc.

Why?

Similar principles apply to behavior as in other scientific disciplines. For an intervention to work, it must meet certain rules and behavioral principles. In sales, you need to solve the customer’s problem; marketing should appeal to emotions, and advertising must be properly targeted.

The same should be true for interventions aimed at changing certain behaviors.

Instead of behavioral solutions, companies tend to repeatedly inform about possible consequences or show the final result of using an app. But have you ever heard someone who caused a tragedy say, “I didn’t know that a child or an animal couldn’t survive the heat in a car”? Or say, “This is the first time I’ve heard that I shouldn’t use my phone while driving or eat that high-calorie cake”?

I assume not.

More often, we see a person who regrets what happened and who doesn’t even really know what occurred in the moment or why they made that decision.

There Is No Universal Guide

Writing long analyses like this instead of brief bullet-point summaries has one major disadvantage: it tends to discourage most people, or they simply won’t finish reading it. However, this type of study is mainly for those who are fascinated by human behavior, who want to learn how to address it in today’s world of technology and AI, or who are truly good in their field and wish to elevate their understanding and see things from new perspectives.

Blogs like this aim to:

explain insights using real-life examples so you can understand why things happen the way they do,

teach you how to practically apply these insights in your everyday life,

serve as inspiration or a resource you can return to at any time.

I realized long ago that internet guides written in bullet points don’t ultimately teach you anything significant, like:

“These 5 steps are all you need to grow quickly”

“10 ways to build a product”

“8 secret principles of successful brands”

From my point of view, all of this is complete nonsense, unless you’re a total beginner in the field and just need a basic overview to understand what it’s all about.

I write these analyses mainly for myself, to organize my thoughts and have a place to record the tools I’ve discovered, tried, and liked. It gives me a source I can return to when I encounter a situation that requires an approach similar to the one described in the analysis.

This isn’t something you read once and forget about. It’s material I have saved and always come back to.

Remember, diagnosing the problem represents 50 percent of success.

How to Define Behavior

At first, I planned to simply break down various areas of behavior in detail and address them directly, creating material specifically for experts—people who are already familiar with the topic. However, I later realized that I shouldn’t just present this in an informational-educational format, but rather in a methodological style.

This means also showing the necessary steps at the beginning—before we even start defining behavior or decisions—so that anyone can understand it.

In other words, I’ll show everything that needs to be done before diving into the actual model.

So, let’s go through it together.

Introduction

First of all, I always define the basic parameters of the project and ask questions like:

What type of initiative is this? (Campaign, product, new service, innovation, new initiative within the company, new product feature, etc.)

What resources do I have available? (Money, materials, people, technologies, etc.)

What is the timeline? (day, week, month?)

And so on.

These are essentially all the basic things that everyone should know about the project—nothing too complicated or specific. Just understanding the project, its resources, and its limitations.

Next, it’s crucial to clearly define the desired final behavior.

Defining the Right Behavior

Behavioral Pattern

To apply insights related to behavioral interventions, you need to start by conceptualizing the relevant behavior patterns that underlie behavioral problems. This is done through the so-called behavioral pattern, which consists of:

Who (“agent”): Whose behavior do we want to change? How many people are in the target group?

Preferred behavior: What behavior do we want to achieve, and what is the current rate of compliance?

Non-preferred behavior: What behavior would we like to change, and what is the current rate of non-compliance?

Context (When/Where): In what context does the behavior occur?

Exercise: How to Fill in the Behavioral Pattern Template:

Try to fill in the behavioral pattern template for the “Hand Hygiene in Hospitals” case.

Hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) are costly for both patients and society as a whole. Contracting an infection in the hospital adds additional suffering for the patient, which, in the worst-case scenario, can lead to death. Improving hand hygiene behavior in hospitals is one of the most promising ways to prevent such HAIs. A hospital in Slovakia is trying to use behavioral interventions to increase the number of visitors using hand sanitizer and has chosen the hospital entrance for a pilot study. In an initial observational study under the current setup at the entrance, it was found that out of 1,000 observed visitors, only 200 used the sanitizer, while 800 did not.

This is the result:

Let’s go back.

When you have clearly defined the final behavior you want to achieve and know where you currently stand, the next step is figuring out how to get there.

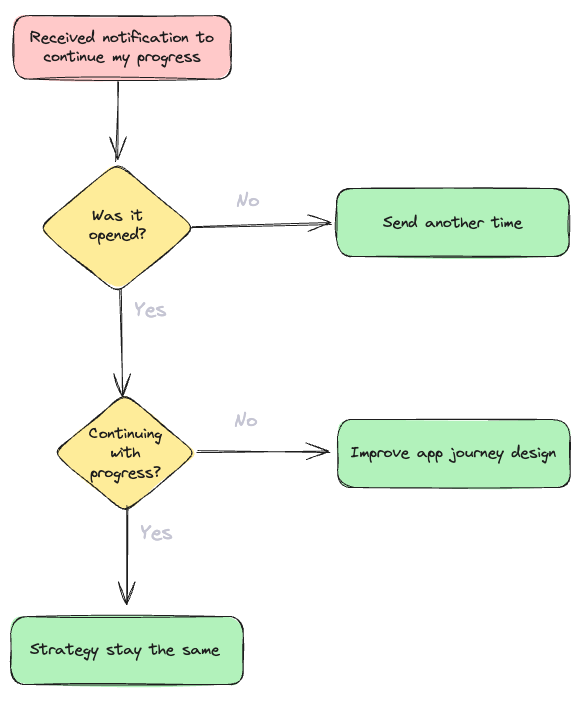

Decision Diagram

What is a behavioral decision diagram?

It shows how the steps in the process fit together.

This is done by breaking the process down into individual activities, illustrating the relationships between them, and showing the flow of the process.

This flowchart provides a detailed description of how the process actually unfolds, as well as data on decision-making, allowing for subsequent quantitative analysis.

Why should you use a behavioral decision diagram?

The simplicity of the behavioral flowchart makes it useful for creating a shared understanding of processes within teams. It can be used to identify the architecture of choices that are crucial for the effectiveness and stability of the process.

A decision diagram is essentially the same as drawing user journeys or user flows, but it places more emphasis on decisions.

For a better idea, take a look at the image below—a screenshot of one of the user journeys for a product we’re building at Sudolabs.

This is why developing a decision diagram is more effective, as it allows you to focus solely on the most critical points of the decision-making process.

Here’s another example, along with instructions on how to create such a diagram:

For those of you who have purchased the ebook, where all these articles are combined—you’ll even find an exercise in the appendix to try building your own decision diagram on a real example, with additional explanations.

Your goal is to identify all decision points, ideally marked with this symbol:

Once you’ve identified the individual decisions, we can move on to the part this entire study is about—categorizing the decisions into the correct areas of human behavior.

Behavioral Framework ABCD

ABCD is an acronym for:

Attention

Belief formation

Choice

Determination

This is an example of the behavioral framework in its simplest form, covering the main aspects of behavior where you can categorize a particular action.

We will delve into the details and understanding of each part in this comprehensive blog.

However, before that, we will explore four major interventions that failed simply because they didn’t understand this framework.

When You Misclassify Behavior

There are two basic things to keep in mind at the highest level: address the correct problem, and address it correctly.

Straightforward, right?

Yet, many people still don’t do it. And why?

Because it’s actually not that simple.

In this section, we will show what happens when you address behavior incorrectly. Not only that, but we’ll also present an example where the behavior was correctly addressed, but the solution to the problem was wrong.

⚠️ Small note: It’s okay if you don’t yet understand why a certain thing is categorized in a specific area. We will cover all of this in detail throughout this study.

Example 1: Campaign Against Phone Use While Driving

Campaigns against phone use while driving, shown on TV, billboards, and similar platforms, have little to no effect on people because they address the “Belief Formation” area instead of focusing on “Choice” or “Determination.”

The issue is—just like everyone knows they shouldn’t drive drunk—people are aware that using a phone while driving is dangerous. However, when someone is in the moment, like when they’re under the influence or distracted, they often don’t make the right decisions. The situation worsens if someone feels the pressure of needing to get somewhere, for example, home, and doesn’t have an easier alternative. This weakens their determination and leads them to make a poor decision.

How should this problem be addressed correctly?

Simpler solution: At the beginning of the evening, give your car keys to a responsible friend or bartender.

More complex solution: Install a device in the car that requires you to take a breathalyzer test before starting the vehicle to measure alcohol levels.

Of course, these solutions can be bypassed, but these examples are meant to illustrate simple interventions.

Example 2: Exercise App Linked to Machines

Exercise apps, including those directly connected to workout machines, are on the right track when it comes to addressing human behavior.

However, the issue is that they focus on the wrong area. This is why we still see so many personal trainers in gyms (in my opinion, maybe even too many).

I’ve witnessed several startups fail while trying to replace these trainers.

The way startups or apps approach the problem is in the “Belief Information” area, but it should be in the “Determination” area.

These apps or similar solutions, even unintentionally, operate under the assumption that people don’t exercise because they don’t know what to do or how to do it, and that they need to track their progress for better results.

This might be true for a small group of people who enjoy and are motivated by exercise. For most people, however, exercising is a struggle that requires a great deal of determination just to get started.

Paying a personal trainer, someone I can talk to, who tells me exactly what to do, points out my mistakes, and whom I don’t want to disappoint, is much more powerful. In a way, I transfer part of the responsibility for my behavior and results to this person.

All these solutions—apps or digital machines—address the “Belief” area when they should be focusing on “Determination.”

💭 One of the reasons why trainers or hairdressers won’t be replaced anytime soon. People are social creatures and value that personal connection.

Example 3: Forgetting a Child in the Car

Let’s take one more example from real life before moving on to the more business-oriented section.

Summer campaigns or reminders from your spouse not to forget your child or pet in the car address the “Belief formation” or “Choice” areas, but the issue is entirely about “Attention.”

We constantly think about it, but then suddenly someone calls us with urgent news, and we forget everything else. Our attention span is very limited.

A simple solution to avoid forgetting something in the car, especially a child? Place your wallet, phone, electronic car key, or anything essential that you can’t leave the car without, in the back under the child’s seat.

Many serious problems have surprisingly simple solutions, whether in the digital or physical world.

By applying these insights, I have significantly improved all areas of my life and have also begun creating better digital solutions.

But now, let’s move on to the last example and then to the study itself.

Bonus Example: The Failed Pizza Startup

In this example, the startup addressed the right area but tackled the wrong problem.

I came across this example in one of my favorite blogs, How They Grow, where they covered the failure of this company in an extensive case study. For those of you who read English, I highly recommend checking it out.

The startup, Zume, aimed to speed up pizza delivery by having robots bake the pizzas directly in trucks equipped with built-in kitchens. This meant that once you ordered a pizza, the delivery truck would head to you, and the pizza would be baked en route.

However, it turned out that making pizza is not that simple, and they couldn’t prepare pizzas in those mobile kitchens that tasted as good as those from a traditional pizzeria. As a result, this startup, once valued at an incredible $2.3 billion, ended up in the startup graveyard.

All that money could have been saved if I had written this study earlier.

Pizza is typically ordered as either a substitute for a regular meal—if people don’t have time to cook or don’t feel like cooking—or as food for social events. So, getting the pizza as quickly as possible is certainly something everyone would appreciate. But you know what’s even more important than speed?

That the pizza tastes good. And that you don’t feel embarrassed about what you’ve ordered when sharing it with others.

This example shows that addressing the wrong problem, even with the right focus, can lead to failure. Taste mattered more than the speed in this case.

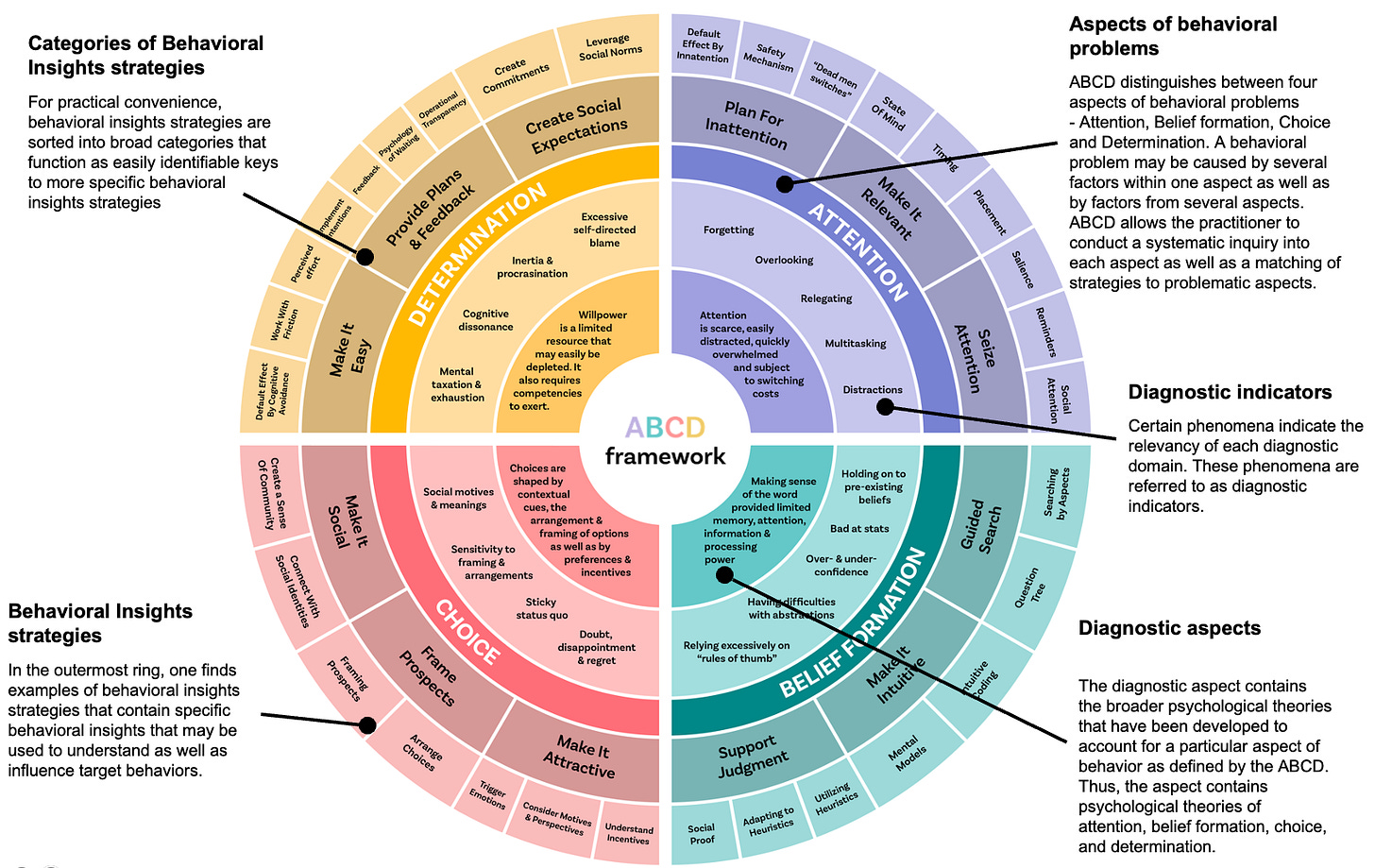

Behavioral Framework ABCD

The BASIC method deals with ways of thinking and was developed by iNudgeyou, a globally recognized firm in the field of behavioral interventions.

This model was primarily designed and used by various corporations and government institutions like the OECD, EU, and World Bank to create better regulations and more effective policy interventions. It primarily focuses on identifying complex behaviors and creating strategies to change them.

What didn’t make sense to me was why this model had to be used in such a complex and large-scale manner. I spent an enormous amount of time studying these methods, exploring how they could be applied in the everyday world of regular people—to create better services, digital products, e-commerce businesses, and much more.

The ABCD framework differs from other ways of thinking about behavior. Instead of offering a simple list of ideas, it helps researchers take a closer look at the behavior they’re trying to understand, breaking it down into different parts:

Diagnostic aspect and indicators: This means carefully examining the behavior and its signs, helping to narrow the focus.

Strategies: It serves as a starting point for finding ways to change the behavior being studied.

Opinions: These are ideas that have worked in various situations and can guide new approaches to changing behavior.

I slightly adjusted this method, added some points, simplified the language, and supported it with visual examples from both the digital and physical worlds—things you commonly encounter—to make this model accessible to anyone interested in these insights.

When you try to identify a thought process, it’s similar to how a doctor tries to figure out what’s wrong with a patient by observing symptoms and running tests.

People studying behavior use a similar method, trying to understand why someone behaves in a certain way by observing clues and evidence. This kind of thinking is called abductive reasoning, meaning the search for the best possible explanation despite uncertainty.

The reason they put so much effort into this is that it helps them create better ways to change behavior. Just as doctors need to understand what causes a disease in order to treat it, researchers of human behavior need to understand why people do certain things in order to help guide them toward different behaviors.

Understanding human behavior is complex, which is why there are so many alcoholics in both professions—just kidding, of course, or am I! 🙈

When changing behavior, the first step is identifying where the problem lies. The ABCD framework (as shown in the image below) is used to define and diagnose the behavioral area (a category of human behavior) where the “problematic” behavior—such as forgetting a child in the car or reluctance to learn a new language—occurs.

As we demonstrated earlier, this is why common campaigns often don’t work, because they fail to address the real behavioral issue, which is essentially the problem of human decision-making and behavior.

For example, if I forget something, it’s not a problem of lack of information, choice, or determination; it’s an issue of attention—or rather, inattention. If I fail at dieting or exercising, again, it’s not a problem of information about fitness or healthy eating, or even a bad choice; it’s a problem of determination, which can be addressed in a very different way.

Let’s briefly summarize all four areas of behavior and explain how you can address them.

Area: Attention - So important and yet so easy to lose

The first area in behavioral fields is Attention. Nearly all of us severely underestimate our ability to maintain it.

What do we actually know about attention?

Human attention is surprisingly limited—in fact, we cannot fully concentrate on multiple things at once. Try solving the math problem 54 x 47 while attempting to park in a very tight spot.

Every time we shift our attention elsewhere, it costs us so-called “switching costs.” One such cost is that when people were interrupted for just 2.8 seconds—like by a colleague’s question or a text message—the number of mistakes they made on a computer exercise doubled.

So, how many mistakes can someone make behind the wheel when their attention is diverted?

If you have to do many additional things before reaching your destination, your brain tricks you into thinking you’ll quickly return to your original focus, which might not be true. Or, it may push something like your pet or child out of short-term memory, and you simply forget about them.

Indicators of this area include:

Forgetting

Overlooking

Degrading

Multitasking

Distraction

Attention is precious, easily distracted, quickly lost, and subject to switching costs.

Area: Belief Formation - It’s not all just about knowledge, plus, even that can be wrong

The next behavioral area is called Belief Formation. This is the area that campaigns primarily target. Campaigns aim to educate people to avoid potential consequences.

But where’s the problem?

The problem lies in the fact that people are already aware of these consequences. If you ask someone who left a child in a car, was late for an important meeting, forgot to turn off the stove, overate, or used their phone while driving if they understand the risks of their behavior, they’ll say yes. We’re human, we act impulsively, and we’re irrational. We don’t need more education or warnings—we’re well aware of the consequences.

This area shows how people try to understand the world despite limited memory, attention, information, and cognitive capacity.

These limitations often lead to poor decisions or inappropriate behavior, which is why this area requires a specific approach as well.

Indicators of this area include:

Holding on to previous beliefs

Poor understanding of statistics

Excessive or insufficient confidence

Difficulty with abstractions

Over-reliance on “rules of thumb” (heuristics)

Addressing belief-related issues requires understanding these cognitive limitations and working within them to encourage better decision-making.

Area: Choice - Our decisions are not entirely our own

The next behavioral area, Choice, is perhaps the most misleading and deceptive. It’s also the most commonly addressed in the everyday world. Problems that initially appear to be conscious choices or decisions often turn out not to be.

People tend to argue: “He chose to pick up the phone while driving, eat the dessert, skip the workout, pass on the career opportunity, or leave the child alone in the car.” While this is partly true, our actions are often impulsive and driven by specific stimuli.

When our phone rings, we often subconsciously grab it without fully considering the risks. Dopamine, so to speak, “hijacks our brain,” and we act under its influence. We react automatically, often without realizing it. When we park the car, we don’t start listing the pros and cons of whether the child can stay in the car, nor do we calculate how many calories we’ve burned before eating a dessert.

This is an area that people encounter the most, and we’ll aim to understand it. However, the goal of this article is to highlight that there are other areas that are often overlooked.

In this specific area, it’s important to understand that choices are shaped by contextual signals, how options are arranged and framed, as well as preferences and stimuli.

Indicators of this area include:

Social motives and meanings

Sensitivity to framing and arrangement

Stimuli and the difficulty of changing the status quo

Doubts and regret

Understanding how these factors influence decision-making helps to shape better interventions and solutions for addressing behavioral problems.

If the way I approach things resonates — or if your product, idea, or strategy feels even slightly “off” — I might be able to help.

Let’s have a quick 20-minute call to find clarity together:

Area: Determination - Help a person overcome their own biological settings

The third area is Determination. Our willpower is a limited resource that can easily be depleted. What do most people do when a campaign reminds them of a problem, such as not driving under the influence or not using their phone while driving? They start telling themselves that they shouldn’t do it under any circumstances. Unfortunately, willpower is fickle, and our cognitive abilities are limited.

It’s important to understand that willpower has its boundaries, which can be easily exhausted. Additionally, using it effectively requires certain skills to apply it.

Indicators of this area include:

Feelings of guilt

Cognitive dissonance

Mental overload

Inertia and procrastination

This was a brief overview of all the areas, which we will explore in detail in the following sections.

- Peter

For those who would like to support this effort, you can find the entire study here for a symbolic price. It also includes examples and exercises that you won’t find in the article.