The Physical Wallet Project Failed - Could 2.5 Years of Work Have Been Solved in 2 Weeks? Yes.

This is the story of a founder who sacrificed 2.5 years of his life for a project that never managed to take off. So what actually happened-and where did it all go wrong? Let’s break it down

For those who want to read the full story, you can find it here:

A post popped up online about a failed product, this time, a physical one.

In my world, nothing new or surprising. I see stories like this all the time. You might be asking…

So What Made This One Different?

Honestly, two weeks of proper work could’ve predicted this failure. Deeper market research, a few tough questions, and it all would’ve been clear from the start.

After the story blew up online, the comments came pouring in. As usual, I agreed with some takes, rolled my eyes at others. A few offered solid advice, but most were just band-aids on a bullet wound.

My take on this isn’t pulled out of thin air. I’ve been through a very similar mess, burnout, business failure, and even a hospital stay thanks to long-term stress. Learned a lot the hard way.

Since then, I’ve helped build products used by millions, advised startups and corporates across different markets, and, just as importantly, watched a few things crash and burn up close.

So when I say this failure wasn’t about bad marketing or a weak e-shop, I mean it.

It was a product no one needed, in a market that didn’t care.

And no amount of branding wizardry can save that. Not even if you hired the team that made canned water cool.

This post breaks down what actually happened, not just the surface symptoms, but the root causes. Some parts will sting, especially if you’re building something yourself.

But that’s kind of the point.

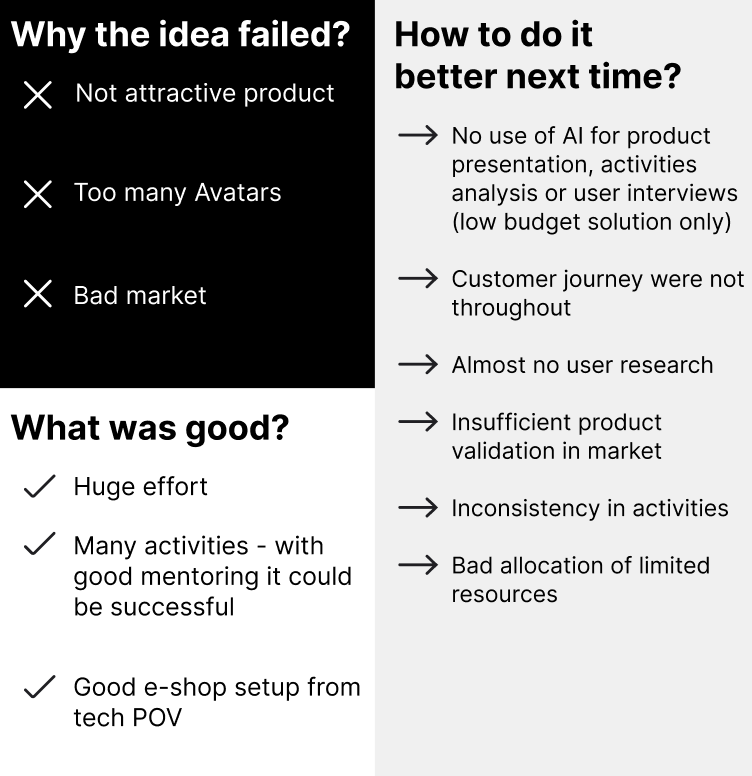

Overall Summary

First off, respect. Seriously, two and a half years of trying? That kind of persistence is rare, and it deserves recognition.

Now, let’s break it down into a few key points: what was done well, and what really wasn’t.

Unfortunately,

The Paperwallet Story

“A Sad End for Paperwallet, Despite All the Effort”

Let’s start with the title.

“Sometimes you win, and sometimes you learn.”

Yeah… no. That’s the kind of feel-good bullshit people repeat just to soften the blow of failure. I know, I used to tell it to myself all the time.

But the truth?

Sometimes you really JUST fail.

And whether or not you learn something from it, and more importantly, how much, that’s entirely on you.

I see people every single week making the same mistakes over and over, and then wondering what went wrong.

So let’s call it what it is:

Sometimes you win.

Other times, you lose hard.

But if you walk away with something valuable, you come out better in the end.

One of my favorite quotes here is from Dr. Robert Burgelman, a business professor at Stanford:

"It is far better to have understood why you failed than to be ignorant of why you succeeded."

I have a feeling the founder of Dedoles would agree.

“Despite the effort”. That part of the sentence highlights one of the toughest truths in business:

Effort alone means nothing.

Most people, especially those doing manual labor, work way harder than consultants. Definitely harder than I do.

And yet, they earn less. Welcome to the brutal economics of reality.

If you’re sprinting a marathon in the wrong direction, it doesn’t matter how fast or hard you run, you’ll still lose.

Misaligned direction and misused resources will kill your outcome.

If someone points you in the right direction early enough, you’ve got a real shot at making it.

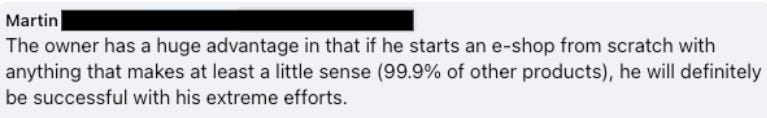

That’s why I partly agree with Martin (from the earlier comments), but not with the word “definitely.”

A close friend of mine has launched about 7 businesses over the years. He’s always worked his ass off, but he’s never managed to break through to something bigger.

But hey, that’s a story for another time.

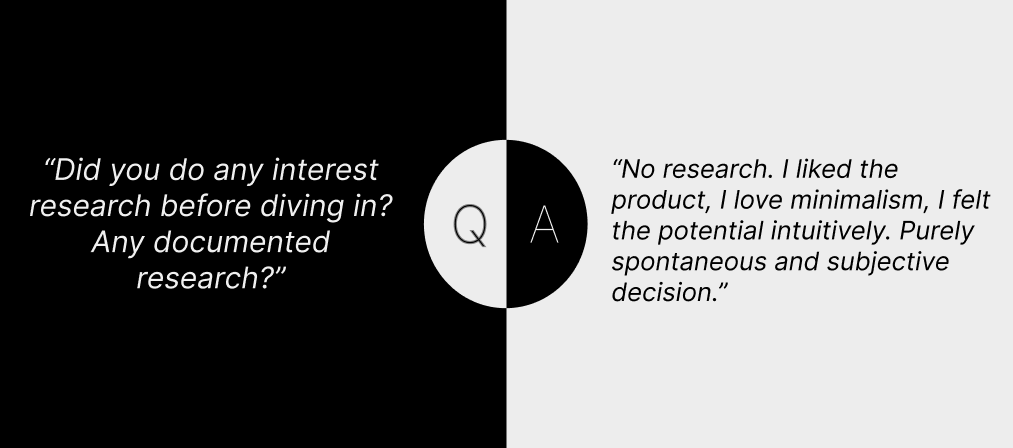

“I first came across the brand Paperwallet in 2020. Back then, the e-shop was already for sale, but the price seemed too high, and I didn’t have time for a new project.”

As soon as I read that sentence, one question immediately came to mind.

This is where I started evaluating what I call founder risk—something I assess with every business I look at. And honestly, every founder should validate it for themselves before diving into any project.

It’s about understanding what skills the founder actually brings to the table—and what they’ll need to compensate for.

If I, as a programmer, were to launch something today in a hyper-competitive market with easy access to e-shop tools, I’d be missing almost everything critical for success.

Technical skills are necessary, sure, but for simple products, like a simple e-shop, they’re more of a bare minimum, not a success factor.

If I were in the shoes of an investor, my reaction to this sentence would be a hard pass.

And look—I get it. People experiment. They learn a ton from the process. That’s not up for debate.

But from a pure, objective standpoint? The founder risk here is massive.

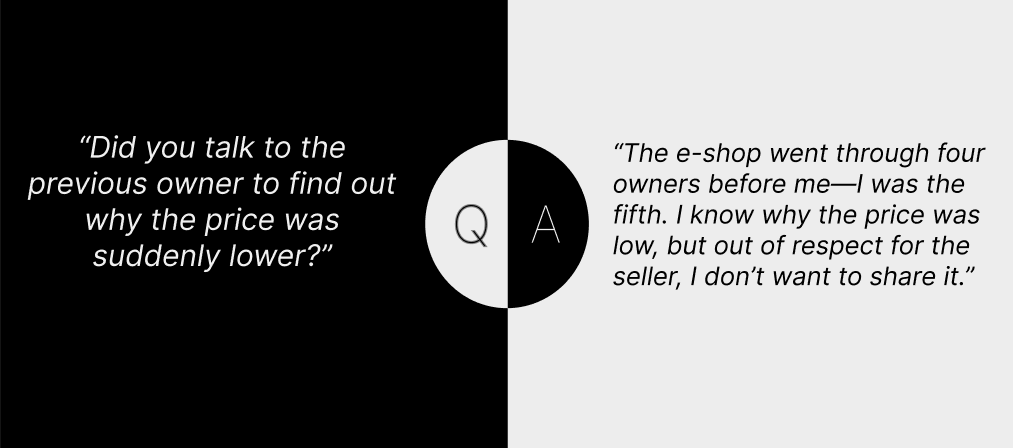

“When the listing popped up again two years later, with a much lower price, I didn’t think about it too long.”

But that’s exactly when you should think long and hard.

This was my first major red flag. So I had to ask a follow-up question.

Anytime something’s up for sale, you need to do a deep dive into why.

In bigger deals, the seller will never tell you the whole truth upfront. My mentor drilled that into me when we were working on a deal worth over €100 million at the start of my career.

You need to dig for the real reason.

Sometimes we even do due diligence on the seller personally, just as seriously as we investigate the business.

“I liked the product, the price was good. One thing led to another, and by May 2022 I had all the access credentials, a few dozen wallets in stock, and my own Paperwallet in my pocket.”

Before I go into the next lesson (one I learned too late myself), here’s what I asked:

We shouldn’t blindly follow our feelings. Intuition can mislead, especially when you don’t have deep experience in the space.

The only time you should trust your gut is when you’re already a seasoned pro who’s seen dozens of similar cases and knows the patterns cold.

Otherwise?

Always verify.

Always.

After this answer, I probably would’ve stopped any further conversation about potential collaboration. But hey—we’re here to learn.

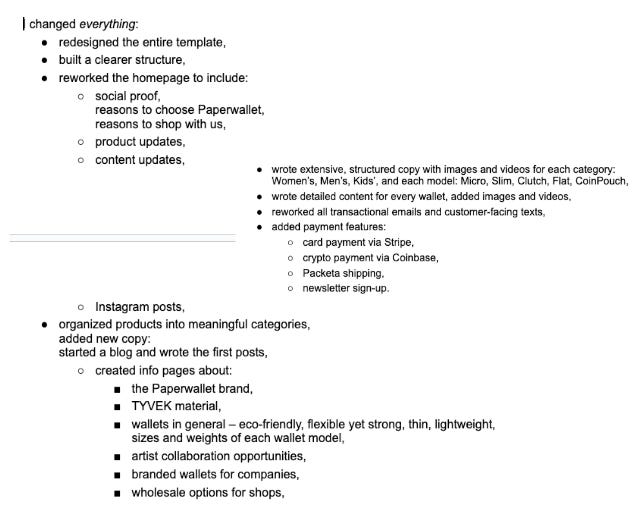

“The technical state of the e-shop was in a miserable condition. The previous owner told me he didn’t pay much attention to the shop and that it only worked for him thanks to some offline sales at a gaming event. I already had a rough plan in my head:

go through every single email to see who the e-shop had communicated with and how it ended,

read through all messages on Messenger and Instagram with the same goal,

bring the e-shop to a functional and content baseline,

get in touch with the HQ in the US and see what other cooperation options we could launch.”

In my opinion, this is a very solid approach.

Although I would expect to see some kind of documented analysis of all this. Including conclusions and hypotheses. But that’s a topic of its own.

“I had about a month before launch.”

“I knew setting up the limited company would take some time, so I got to work. In emails and social media messages, I found a few contacts worth reviving. One satisfied customer sent me a photo of their wallet after five years of use (I added it to the references), and I arranged a promo post for launch day with travel influencer Dominika, IG @cestujspoznavaj.”

The sentence that caught my eye was:

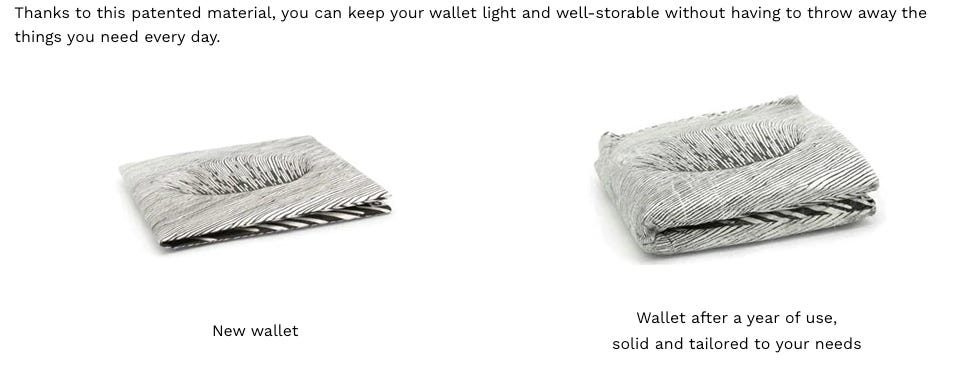

“A satisfied customer sent me a photo of the wallet after five years of use (I added it to the references).”

I’m not a marketer, but what I would’ve done is call that customer and ask them to take better-quality photos (and tell them how to do it). Then I’d create a carousel ad campaign, include a photo of the new wallet, and follow it up with the aged one to show how it holds up after all those years. I’d try turning it into a small marketing campaign.

At the very least, as part of A/B testing.

I’ve seen several brands do this, and it works very well — and here, it was basically served on a silver platter.

“The e-shop lacked basic functions and information. You couldn’t pay by card, cash-on-delivery wasn’t available, and there was no Packeta integration.

There was no basic information about the wallets in general, or the material they were made of. I had access to photos and videos from the HQ for every wallet, but they were missing from the product pages. I added detailed descriptions with features, parameters, and info about who Paperwallets are suitable for.

The homepage lacked key elements and information. There was a lot of work to be done. While I was making adjustments, I started reading: 55 Tips for a Successful E-shop, The Secret Diary of an E-shop Owner, SEO Basics, Creating a Profitable Blog, Step-by-step Guide to a Profitable Website, and I joined marketing and ecommerce groups—anywhere I felt I could learn something.”

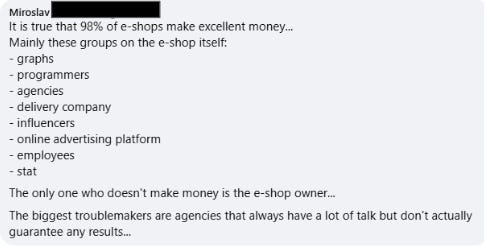

There’s a lot to unpack here. And maybe this will sound harsh, but this is the perfect example of why I stopped doing behavioral analyses:

“You can’t turn shit into a chocolate cake, even with the best icing.”

Clients used to expect me to tweak wording and buttons to “convince” customers to buy.

But when I looked under the hood, I realized the whole product, the process, and everything around it was crap.

That’s why I moved into product work.

And this quote really captures the essence.

Especially when people don’t know what they’re doing.

When I run workshops or talk to folks, I’ve lost count of how many times I’ve heard that some agency wrote them a “marketing strategy” — 50 pages long, expensive — and no one in the company knows what to do with it.

For the same reason, my own 30-page behavioral reports were useless too — poor eshop owners had no clue where to even start.

Just like this article — it’s too long. But if you’ve got money and no time, you would hire me or someone like me.

If you’ve got time and determination but no money, these articles are for you.

“Sales activities I worked on:”

Massive respect for how many activities you tried, but to be honest, it feels like the project was funded by investors.

It actually reminds me of myself back in the day, when I used to create workshops and services before I even sold them. I once made 1,200 slides… and didn’t sell a single workshop.

Nowadays, I usually first agree on a workshop topic that suits the client, and then I create the content. And yeah, I can afford to do that now, because I’ve got nearly a decade of experience and those 1,200 slides plus 2,000 pages of material and research ready to go.

By the way, Steve Jobs was also known for selling something first—or closing the deal—before figuring out how to actually build it.

What would I have done?

I’d first define my customer “avatar” (more on that soon), ask my grandpa to build me a booth, and just go sell it at an event where my target audience hangs out.

Alongside that, I’d create a super simple landing page—focused on just one product, maybe 2–3 use cases depending on the target group. Then measure, test, adjust… measure, test, adjust.

“The e-shop’s HQ is near the Czech border, so I adjusted the template and texts to make sure Czech customers would see prices in CZK and would have price info at every step of the purchase.”

I’m not an expert here, but I know enough to say—this is not how Czech customers buy from Slovak e-shops. They expect everything to be in Czech, ideally with a fully Czech e-shop. Just switching the currency to CZK probably isn’t enough.

But now I’m stepping outside my area of expertise. I just need to know what to look at, and what risks to verify—and I’ve got the right people around me to help. That’s exactly the kind of people you need to start finding.

And really, anyone doing business should think this way: spot potential risks, and realize that just flipping prices into Czech koruna most likely isn’t going to cut it.

“I installed Smartlook, Analytics, pixels, and launched the e-shop on July 1st, 2022.

Time to chase customers.

Dominika posted the story, reel, and photos as agreed, and the first order came in. Awesome.

I contacted every customer who had placed an order with the previous owner and sent out the first newsletter to seven addresses. I reached out to everyone who’d ever interacted with the shop. I went through all the old messages on social media, followed up, and replied to previously unanswered questions. I also checked all the old emails and either responded or reminded them the shop was back online.”

Not much to add here—it makes sense.

“Based on the wallet’s features, I figured out who my target group was.”

Honestly? Not a bad approach. I mean, everyone would do something like this.

But in my view, it would’ve been even better to have documented interviews with at least 20–30 potential customers. From there, create analyses, hypotheses, and conclusions.

The kind of work no one wants to do.

“Lightweight, slim, water-resistant wallets are ideal for people doing sports—running, cycling, hiking, fishing, hunting, skiing, etc. Great for travelers—minimalism helps, and RFID protection is a bonus abroad. Artist-designed styles appeal to fashion lovers and young people. The eco-friendly and durable TYVEK material targets fans of slow fashion and sustainability.”

Now we hit one of the classic problems most businesses run into—including my first consulting venture:

Too many avatars.

Too many customer types the business tries to target from the start.

Why do businesses do this? Because they want to make money. The logic seems obvious: the more people you target, the bigger the reach, the more traffic = the more sales. Especially in the early days, when every euro counts.

But that’s the paradox of business, especially with niche products:

If you try to speak to everyone, you end up resonating with no one.

It’s not bad to go broader later. But in the beginning, especially with products or services people don’t already know, you need to aim super precisely.

So precisely that you could even narrow it down to one specific sport.

Early-stage products, especially with limited resources, need a tight niche.

And you need to treat your resources with what I call surgical precision—that applies to your marketing too.

So if it were me, I’d pick one avatar—say, people who go hiking.

I’d focus just on them for weeks: their problems, needs, habits.

(Hypothetically speaking—I don’t know if that’s the best target group.)

For those of you who want to dive into how to choose the right avatar, or how to even think about this stuff at the start, I highly recommend this checklist from Alex Hormozi. He’s one of my favorite business thinkers and a huge inspiration.

And to be completely honest, I still struggle with choosing the right avatar. Even now.

Which is exactly why I know so much about it—because I’ve fucked it up myself. Many times.

“I set up collaborations with:”

Athletes – Novodubnický Cycling Marathon, Cross Run Opatová, field hockey tournament in Prešov, and others

Travelers – Dominika from @cestujspoznavaj

Ecology – supported the Waste Management Ball in Bratislava

Young generation – supported dozens of high school events – proms and balls

Again, I might get some hate from marketers for this, but in my view: complete nonsense.

As I mentioned earlier: when you have limited resources, you operate with surgical precision.

This is like if a surgeon brought a TV into the operating room, turned on his favorite show, and started streaming and answering live questions from viewers mid-operation—attention completely scattered.

This is like if a surgeon brought a TV into the operating room, turned on his favorite show, and started streaming and answering live questions from viewers mid-operation—attention completely scattered.

This is the kind of thing established brands do to expand brand awareness in consumers’ minds. Hopefully, you figured this out on your own, because if someone advised you to do this, they should immediately return their imaginary online marketing certificate, which was most likely free.

If you came up with it yourself, fine, you’re learning. But don’t ever do this again. It’s a huge waste of energy, time, and money.

And that line, “ecology – supported the Waste Management Ball in Bratislava,” honestly made me laugh.

If I were doing the marketing, I’d go into sharp performance marketing—constant A/B testing of creatives until I hit the right one.

But personally, I’d probably go more offline: for example, give away wallets for free at an event, with a note inside offering 50% off the next purchase. And if people don’t use it (and by that, I don’t mean buying another wallet, I mean recommending it to someone else), then I know I either need to find a new target group, or my product just isn’t that good.

In today’s world, where AI can create your creative assets and your website, if you haven’t tested something deeply with real people (and almost for free), it’s not even worth talking about it anymore.

“There were many more collaborations, and the results were still weak.”

This sentence speaks for itself.

What brings down a founder usually isn’t the product—it’s their own flawed mental models.

That’s exactly what happened here.

You were brought down by the exact thing one community member commented on.

I’d honestly read a whole article on this phenomenon, because your story is a textbook example of the theory.

Business isn’t just about good products—it’s about how people think.

It’s about the founders themselves. That’s the difference between someone who’s built five successful companies and someone else who still doesn’t know how to do a decent behavioral analysis at the beginning of their journey (yes, talking about me).

But we’re here to grow—so let’s keep going.

“The only collaboration that went really well was with Silvia from @Minidiamondblog. She tried the wallet, loved it, recorded a beautiful and insightful video. When she published it, the shop’s traffic shot up and orders were coming in every two to three minutes. It was a wild ride.

I also had a great collaboration with Filip @filippreston on TikTok, with Dominika @cestujspoznavaj, and others. But it still wasn’t enough to create a real breakthrough.

I looked for exposure opportunities everywhere. I listed the shop as a KauflandCard partner, arranged and supported discount coupons for dozens of prom nights, New Year’s parties, and elegant balls. From high schools to hotels to large companies and organizations across Slovakia. The result? Zero. Kaufland brought in a few orders, otherwise nothing.”

I already explained why this whole approach doesn’t make sense, so instead of repeating myself here, let me just drop an AI-generated image that sums it up better than words ever could:

It doesn’t matter how much water you pour in—if you don’t plug the holes, it’ll all leak out.

“Kaufland was already a big player, but when I landed a sponsorship deal with the Cinemax cinema network for their Ladies’ Night event, I really thought this would be the breakthrough. A targeted audience—3,500 women across 14 theaters would get a €10 coupon for a wallet purchase and a flyer outlining the awesome features of the Paperwallet. I went even further. I brought a photo frame and funny signs to each theater so the women could have some extra fun. And of course, I added three discount raffle coupons for each location. The result? Nothing. A week after the event, not a single coupon had been used. Over the course of a year? Maybe six. Eventually, I deactivated the offer. I tried arranging another partnership with Cinemax, but that fell through too—the original contact left, and the new one never replied.”

Nice idea and creative execution—but equally a waste of time.

This is marketing that barely works even for big brands.

This happens when marketing is done without understanding behavioral principles.

I strongly recommend reading my study The Ultimate Guide: A Model for Identifying and Changing Behavior – Introducing the ABCD Framework.

Yes, it’s dense and could’ve been written more simply, but I spent weeks on it, and it contains insights that are crucial even for offline marketing.

One key concept I mention there is “state of mind.”

People often launch marketing campaigns just because they saw someone else do it.

They might even be creative about it, but it’s all for nothing.

Why? Because it’s delivered in the wrong context or targets a customer in the wrong mental state.

Let’s go through a basic thought process:

What’s the mindset of people going to the cinema?

Even more specifically, women going to a “Ladies’ Night”?

They’re looking for fun.

They’re finally getting a break with their friends. They want to laugh, catch up, maybe show off something new in their lives.

They’re there for a lighthearted, feel-good movie.

It’s all positive emotional energy.

That’s also what their RAS (Reticular Activating System) is tuned into. (I highly recommend learning more about RAS—it’s one of the most powerful mental filters we have.)

So anything that doesn’t support that emotional context?

Their brain will automatically filter it out.

Even if someone handed me a flyer—something “mostly annoying”—maybe I’d chuckle at it… but then I’d forget about it. Instantly.

For something to actually catch their attention, it would have to solve a problem they’re actively dealing with at that very moment.

And you said the product is meant for athletes or artists.

What the fuck does that have to do with a cinema and a ladies’ night?

Another thing—you should know (and if you don’t, now you do):

From an evolutionary perspective, women care more than men about how they’re perceived socially.

That’s why they naturally want to dress well and present themselves in the best light.

And in Slovakia? That’s twice as strong—here, “showing off” often beats common sense.

Your product isn’t visually appealing enough.

Even just putting your flyer in her handbag might signal she has bad taste.

Is that sad? Yeah.

But we’re not here to fix society—we’re here to understand how customers think.

That comment really made me laugh, and I agree 100%.

McDonald’s reported that customers spend 15–20% more on average at self-service kiosks.

Why? State of mind.

More time to browse, less stress (no line behind them), and most importantly, they don’t feel judged by the cashier when they add a sundae with extra fudge to their meal.

This is a perfect example of how important mental state is, and how our social and evolutionary wiring shapes decision-making.

Wrong situation + wrong product = bad combo, sorry, really bad combo.

But I’m not just here to criticize—I want to show you why it failed.

“A few other partnerships ended the same way, so I gradually stopped. A week-long campaign and contest on national Dobré rádio, a feature in the ‘Gift Ideas’ section of the Christmas issue of Evita magazine, an appearance in a TV Markíza segment on eco-living, a collaboration with Repetito.sk—reusable envelopes. We were even the first e-shop in Slovakia to use them.”

At this point, with so many activities, it’s not admirable anymore—it’s starting to get sad.

“Just take the L, bro.”

What’s missing is mentorship.

Next time, please get a mentor.

Not talking about me.

Just someone who can give you straight-up feedback from the beginning.

“What was a major disappointment were eco-influencers, politicians, and organizations focused on sustainability. I contacted dozens, pitching a new product on the market—an eco-friendly wallet made from recycled and recyclable materials, with artist collaboration. A shop operating in the most sustainable way possible—no material or energy waste, minimal packaging, and pro-nature gestures like using a staple-free stapler. Nobody replied.”

This is my favorite part.

Maybe even the final straw that pushed me to write this article.

And yeah, I’m going to go in hard here—it’s gonna trigger people. Rightfully so. This part hurt me personally. I’ve been burned the same way.

So what did I learn?

Don’t listen to what people say—watch how they behave.

Forget what they claim to want—observe what they actually respond to.

People are, at their core, selfish.

Even those who play saints online—the “planet saviors”—usually do it for attention or validation.

There’s a lot of research supporting this, but I won’t get into that now.

Let me give you the best example:

I once went on a date where the girl scolded me for buying water in a plastic bottle.

Meanwhile, she worked in fashion, bought clothes every other day, and posted about shopping for “zero-waste” food on Instagram.

When I told her fashion is the second most polluting industry on the planet, she got mad and stopped talking to me.

I’ve seen this play out again and again.

That’s why I don’t even bother confronting it anymore—I just write about it here.

For years, I’ve been helping my mom with the charity work she does alongside her business.

So I meet a lot of wealthy people. And guess what?

None of them feel the need to announce to the world what they do.

They don’t preach. They don’t post about it for likes.

They don’t go around telling others what to buy.

Even the Bible says something like:

If you do good and then tell everyone about it, it loses its value for your soul.

So treat these people like any other business partner.

They also want to know what’s in it for them and whether it makes them look good.

And honestly, your not-so-sexy wallet won’t help their image. The only difference in dealing with them?

Wrap your pitch in a nice story—make it sound like they’re saving the planet.

Don’t get me wrong—I still support people doing good. But most of them are builders, not influencers.

Then there are the people I believed in all these years. The ones who say all the right things.

They seem supportive, give great feedback, say how amazing it all is…

But when the moment of truth comes, when you ask if they’d actually pay or support the thing?

Silence.

Or the classic:

“It’s not quite for me, but I’m sure someone will support it—it’s great for the planet.”

This usually happens with family and friends.

Everyone says it’s awesome, but no one’s willing to put down money for it.

And where do people spend their money?

That’s the ultimate signal of true interest.

I’ve seen so many people get burned by this. And the saddest part?

Even when you confront them—they don’t see a problem. No self-reflection. No awareness. Which is why… it’s not even worth dealing with.

There’s no better summary than this comment I once read:

A great product no one understands, someone “gets it,” but still doesn’t buy.

As Slovak rapper Separ once said:

“He won’t support what he enjoys, but still wants the album to be flawless.”

Don’t believe people’s opinions unless they’re willing to put money where their mouth is.

I see this all the time in badly run user interviews during product testing.

People say what features they’d want…

Then I ask if they actually use those features in apps that already have them, and they say no.

With some ridiculous excuse. After about the 25th interview, I started filtering everything differently.

Before that, I took every word at face value.

Once you start noticing these patterns, you get a pretty brutal wake-up call about how people actually behave—and what really motivates them.

““I’m going offline.”

“I realized that Paperwallet is one of those new products that needs to exist in the physical world, because I just can’t sell that surprisingly low weight or the pleasant tactile feel of the material online. People need to touch the product. I bought a sales booth, printed a 4-meter-long PVC banner with the logo, and headed out among the people.”

Can you not sell a feeling?

That insight is almost right, but a good marketer can sell any feeling online. I’ve seen it done with everything. And yes, low weight and a pleasant touch can absolutely be communicated digitally.

That said, going offline? I actually suggested that at the very beginning. So, hey, at least you eventually got there.

“We sold a few wallets at sports events, and then I started looking for brick-and-mortar stores that might include them in their offerings. At its peak, the network had 10 partner shops—7 in Slovakia and 3 in Moravia. From Spišská Nová Ves to Olomouc.

Albi, Panta Rhei, Martinus, Sportissimo, A3, Intersport, and other major chains didn’t respond to emails (the sports ones) or rejected us (the others). Despite zero risk—it was consignment-based.”

This shows a basic misunderstanding of business fundamentals.

There’s no such thing as “zero risk.” Especially not for large retail chains. In fact, for them, it wasn’t just risk—it was also a cost.

I’m surprised anyone even replied to you, as you mention later.

Let me tell you a legendary story:

A young Warren Buffett was blown away by the book The Intelligent Investor and dreamed of learning directly from its author, Benjamin Graham.

So after graduation, he wrote Graham a letter. He offered to work for him for free, just to learn.

Graham declined with a legendary reply:

“If something is free, it’s still too expensive.”

Now imagine this:

A store has spent years building its brand, investing millions into logistics, retail presence, and infrastructure. It hires experts for everything from product strategy to sales optimization.

Then along comes a guy who says:

“Hey, I’ve got this wallet. It’s not selling very well. But I’d love to use the tens of millions you’ve invested—your shelf space, brand equity, retail staff—and maybe squeeze this into a corner somewhere. Instead of golf balls, maybe? Oh, and don’t worry—it’s free. I mean, it’s not working for me, but maybe it’ll sell if you give it a shot…”

Put yourself in their shoes.

That’s probably how they saw you.

In reality, you should’ve paid them just to get a reply.

I’ve been closing deals in the startup space for four years, and here’s what I know:

You never answered the most basic question:

What’s in it for the other side?

And even more importantly:

Why should they even bother?

I could go deeper, but I think you get the point.

Even one word gave it away:

“Despite being free…”

That shows a lack of understanding of basic business logic.

“Free” still costs something when it takes up space, energy, or focus.

“We had an e-shop and 10 physical stores—including two in Bratislava, one at Aupark Garage Popup and one at PlaceStore in the city center—and still couldn’t even average 3 orders per day.

To make it sustainable, I needed to sell 6 a day online, and another 6 across all shops combined.

Despite low sales and high costs, we went to the festivals Pohoda and Grape 2023. The audience was our demographic, and people tend to spend more freely there. We sold around 200 wallets. We didn’t lose money—in the end, we just broke even.”

You know what’s missing here? One simple sentence.

“I spent hours interviewing people who bought the wallets and gathered valuable insights.”

The absence of that says a lot.

It shows a block when it comes to listening to your customers.

Maybe you did talk to them. But if you never mentioned it once, it clearly wasn’t that important to you.

And I’m not listening to what people say—I’m watching what they do.

“Neither offline nor online”

“They’re not selling in stores. They’re not selling online. The content I’m making for social media has zero reach. Nobody’s watching. Nobody’s reacting. No engagement—doesn’t matter if it’s educational, funny, eco-themed, or behind-the-scenes. Did you know Paperwallet can hold an 80kg man? That video has 64 views after two years. It’s demotivating.”

I watched that video you sent.

And look—I’m no creative director, but that video?

It’s bad.

It feels like something from 15 years ago.

A 20-second clip that’s neither a Reel nor a TikTok—it’s just an old-school YouTube-style upload. There’s no creative energy.

It reminds me of those chiropractor videos showing how to sit properly at a desk.

And to be honest, I didn’t even realize it was a wallet.

Everything about it was wrong.

Here’s what I’d suggest next time:

Spend at least 20 hours watching Instagram Reels or TikToks.

Analyze what catches attention. What’s repeated. What works.

Then—and only then—make your own.

You said this whole thing “felt demotivating”.

Which means you were expecting more.

And that’s exactly where the disconnect lies—between your idea of execution and the actual reality of what good execution looks like.

“This is where the fun ends—I contact my first agency.”

This is like when a couple’s relationship is falling apart and someone says:

“Let’s have a baby. That’ll fix things.”

Classic denial of reality.

That’s exactly what this move looks like.

Instead of fixing the fundamentals, you layered something new on top, hoping for a miracle.

“I wanted them to assess the e-shop: is everything OK, should we improve anything, is the site ready for traffic from paid campaigns? The result—burned money and zero increase in visits or sales. Not because the conversion rate was low, but because the campaigns didn’t bring anyone to the e-shop.

We tried different creatives, videos, copy…”

“No matter what I did, traffic was painfully low. Some days—literally zero visitors, even though the shop was live for over a year. But when someone did visit, they bought.

I had a 25% conversion rate—like, 4 visitors and boom, an order. So logically, if I get more visitors, I’ll get more sales. Encouraged by the exposure at festivals, we launched another online campaign.”

Yes—the logic is fine.

You weren’t thinking incorrectly.

But sadly, the math doesn’t check out.

You just didn’t have enough data to draw any real conclusions.

The sample size was way too small. For all you know, those four visitors could’ve been your family feeling sorry.

I’m exaggerating—but you get the point.

“The second agency steps in. They love the product, they vibe with the eco angle and the designs.

Their goal? 25 orders a day.

I asked if anything needed to be improved—UX, UI, anything.

According to them, everything was fine.”

Ohhh nooo.

This feels like:

“Honey, that newborn phase was actually kind of sweet. I know our relationship’s a mess… so what should we do? Let’s have another baby.”

So, according to this second agency, everything’s okay?

Here’s the deal:

If you want quality work and don’t want to burn through your budget, hire individual specialists—and learn from them. Agencies are expensive for this kind of early-stage experimentation.

Also, very few agencies will tell you your idea doesn’t make sense. Most will happily nod, tell you it’s brilliant, that they “totally get it,” and that they already have a clear vision…

“…but of course, please pay in advance.”

It’s like GoBigName—they’ve got amazing marketing about how important brand naming is. And this isn’t a diss on Mišo—we know each other, I like him a lot, and I genuinely think he does great work.

But I know people who spent big on a name—and then didn’t have enough left to actually do anything else.

Names matter, yes. But sometimes there are more important things.

We nearly did the same. We almost spent a chunk of our brand’s early budget with GoBigName. Thankfully, we realized we were about to risk everything else just for a name.

So I spent a week on it, came up with 90 combined name options, and a bit of luck—and now we’ve got a great name for basically zero cost (well, my time, yes). I just knew what to look for—and today, we’ve got AI to help with the research too.

Whenever someone tries to sell you something, always ask:

“What’s their motivation?”

A marketing agency will do anything to get you on board because they know that if they launch any campaign, it’ll bring some results. Later on, when it flops long-term, they’ll say:

“We did our job. The product is the problem.”

And sadly? They’re not wrong. Which makes it the perfect way to cover their own backs.

Uber wants you to stay home.

Hospitals don’t want you completely healthy.

Netflix wants you in bed watching shows.

Airbnb wants you to travel.

Absolut Vodka wants you partying.

And me, selfishly?

I want others to fail at solving your problem.

So you realize how hard it actually is.

And in the end… maybe you’ll come to me.

“We started in August to get ready for Christmas 2023. I gave them full creative freedom, told them they could go bold—I’m not a corporate, I have no rules.

The result? No increase in traffic or sales. And a clear loss of interest on the agency’s side.

The sentence ‘I don’t know how to position this’ still rings in my head.”

That’s the kind of sentence that will stay with you forever.

But it’s up to you whether it echoes in your head as a painful failure or as a reminder that you have to be the one who figures this out next time, with your customers or with a few sharp mentors.

Not waiting around for a marketing agency to save you.

“I don’t know how to position it.”

Translation: Usually you need to be the one who positions it, who sets up the vision, and guides agencies.

Not the other way around.

“When I couldn’t even sell during Christmas, I knew it was over. I let go of all my visions, kept the shop running on autopilot, still fulfilling orders and occasionally posting something on social media. On July 1, 2024, I’ll shut down the Slovak e-shop.

In November 2024, I lost the .sk domain. And now I know I’ll shut down the hastily thrown-together Czech version at www.paperwallet.cz too.

Buy the whole thing—or just a wallet.”

Honestly?

Donate the wallets somewhere where they could actually help—shelters, charities, people who truly need them.

I know you’ve got money sunk in them, but maybe it’ll ease the weight on your soul a bit.

And here’s one piece of advice: if you do that, don’t post about it online.

Let’s now take a look at the final section—the analysis of the individual activities and materials you sent me.

We’ll break it down from a behavioral perspective and dust off some of my old tools.

Behavioral analysis of selected materials

The article’s already long enough, so I’ll just focus on some of your activities, mainly ones that aren’t overly specific and can be useful to others reading this, too.

What I try to explain to my clients is that the game has changed. The principles still hold, but the way we execute them is on a whole new level.

That’s why it’s not enough to just copy others. You need to understand why they’re doing it, what they’re trying to achieve, what principles they’re applying—and then do your own version of it, but in a highly creative way.

But enough philosophy—let’s get practical.

Customer Reviews

At first, I wanted to critique the review date and purchase date. But then I realized it could actually have a surprisingly positive effect on people. Maybe it’s even a good idea I’d never considered before.

So yeah—I learned something valuable here.

Of course, I would’ve taken it further and added some well-crafted marketing-style stats.

That aside, I think it’s done quite well. No need to go into extreme detail here.

Wallet Benefits

The fact that something’s patented is cool, but as a customer, I don’t really care; even more, I don’t even know what that should mean for me in the first place.

Maybe if I was an investor, that would be different.

But these are all generic benefits that no longer mean much to the modern consumer.

Try bringing them to life with concrete comparisons—ideally, ones tied to your avatar.

That’s where having a well-defined avatar becomes really important.

I’m just spitballing here, so don’t crucify me, but something like this:

“Tyvek strength – this wallet will survive a mountain downpour during a climb, a fall from a rock wall, and still let you pull out cash for that beer at the mountaintop cabin.”

These are relatable benefits, the kind your target audience (avatars) can see themselves in.

Example of differences

When I saw this, I got excited—because it’s a perfect example of why copying something without understanding the behavioral reasoning behind it doesn’t have the same effect.

This is what you had on your site:

Here, the behavioral principle of comparison is being (mis)used—or more accurately, not used to its potential. This principle states that people can’t make decisions in a vacuum—they always need something to compare them to. This applies heavily to before-and-after visuals as well.

The wallet brand Bellroy used this principle brilliantly on their site and created a slider:

On the left, you see a competitor’s wallet, on the right, Bellroy’s. As you drag the slider, more cards are added to both wallets, and you visually see how each wallet expands, clearly demonstrating the difference.

Here’s a snapshot from one of their campaigns.

It’s amazing.

So what makes theirs better than yours?

First of all, Bellroy addresses and visualizes an immediate, relatable problem—a bulky wallet. And let’s be honest, that’s a pain point many people have.

You, on the other hand, are showing a problem that only emerges after a year of use. And most people don’t even have a mental reference for what wallets look like after a year. That brings us to the second difference.

Bellroy compares its wallet against the “competition”—or rather, a problem they solve better than the competition. So the user immediately thinks:

“Oh damn, I don’t want a wallet that big.”

Paperwallet, in contrast, compares the product… to its own future version, leaving the user in a bit of a mental vacuum. Uncertainty creeps in:

“Is that how a wallet should look after a year? Is this good or bad? Do I even have this problem with other wallets after a year? Is there a big enough difference for me to care?”

The idea itself was heading in the right direction, but this is exactly where the downside of reading those typical short blogs like “6 tips to crush any e-shop and become wildly successful” shows up.

Dimension Table

The same principle applies here:

Instead of showing me a dry table with measurements, show me a visual sketch of a pair of jeans. Show me where the wallet fits in the pocket.

This is like browsing shelves for a kitchen—I want to see how it fits, not study centimeters.

Same for weight.

Compare it to something real:

“Feels lighter than your phone. Roughly the weight of two tea bags.”

Save me cognitive effort as a customer. The less I need to think about the details, the more brainpower I have left to enjoy the idea of owning your product.

Eco-benefits – how you’re saving the planet

These numbers don’t mean anything to people. They can’t visualize them at all, so they won’t have any emotional impact.

The ones who pretend to understand ecosystems might go, “Wow, impressive numbers,” and that’s where it ends.

You can say that Coca-Cola and other drinks contain 30g of sugar…

Or you can do this instead:

Now ask yourself: which one hits harder emotionally?

Raising awareness

Like I mentioned earlier, I absolutely don’t understand this decision.

The next step would’ve been running a TV ad during prime-time evening news.

These are the kind of campaigns you’d expect from a multi-million-euro company.

Cinema campaign

Experts might bash me for this, and I’m not even claiming to be one, but to me, this campaign feels like something cooked up by the HR department of a giant corporation from the head of a 50-year-old woman who came back to work after maternity leave for two kids. Not dissing her at all, just the relevance of the idea.

I honestly don’t see what this has to do with wallets.

What you need are creative, targeted campaigns, with strong associations that make wallets pop out at first glance.

Overall view of the e-shop

There are too many deeper issues elsewhere, so analyzing the e-shop is kind of pointless here.

In itself, the shop isn’t terrible, but it’s not good either.

It looks like a long-standing e-shop with a large product catalog and loads of customers. That’s the impression, judging by how “busy” it feels, and the lack of any creative soul.

There’s nothing imaginative, nothing that gives me the feel of a local brand.

Take Angry Beards as an example—their whole shop had such unique communication (now they’re bigger, so not as much as before), but back then, you could feel the soul of the brand everywhere.

Next time, I’d suggest focusing on one product, one target audience, and tailoring all communication to them. Then gradually expand.

And no—it’s not easy. I struggle with this myself.

I often get labeled as a “general” consultant, and people don’t really know where to place me.

That’s exactly why I write these articles—so someone can go:

“Aha, I know exactly when to use this guy.”

That’s way easier than me trying to chase them down.

But 10× harder to execute.

So don’t take this as me acting like I’ve got it all perfectly figured out. I’m constantly working on it too.

And that’s why I understand the mistake you made—because I’ve made it too.

Final words:

I hope you enjoyed the article. It was a challenge for me, too, since I’ve never really considered this kind of format before, but the opportunity presented itself.

And if:

You’re an (even a beginning) entrepreneur trying to quickly validate your idea and identify potential risks,

You’re a founder aiming to take your startup to the next level,

You’re a business owner building a product with real potential and real benefits for people,

Or you’re a company looking to adapt to today’s world of AI and changing user behavior,

…then reach out and let’s book a short 20-minute call. We’ll see if your challenge is something I can help with effectively, and I’ll make sure it’s something where I can actually make a difference.

If the way I approach things resonates — or if your product, idea, or strategy feels even slightly “off” — I might be able to help.

Let’s have a quick 20-minute call to find clarity together:

I only take on a very limited number of clients because I’m not your typical consultant. I try to stay as hands-on as possible, not just throwing PowerPoints around.

See you in the next article.

— Peter