[4/6] Ultimate Guide: Model for Identifying and Changing Behavior - Choice

Are Our Decisions Truly Our Own? A question I’ve been asking myself for years. Let’s take a closer look at what drives our decisions, what influences them, and, importantly, how we can change them.

Welcome to the fourth part of our series where we explore the ABCD Framework, either as a whole or in individual parts.

We’re already past the halfway point, but we’re not slowing down—not at all.

For those of you who want to explore the previous sections:

[1/6] Introduction to the ABCD Framework

In the previous article, we explored the topic of Belief Formation. It was likely one of the shortest sections, primarily because a lot of resources and information on this subject have already been written and explained in detail online. That’s why I opted to include links instead. However, that won’t be the case with the other areas—quite the opposite, in fact. In these sections, I’ve added content that’s missing from the official model.

Just as a reminder, here’s the full model:

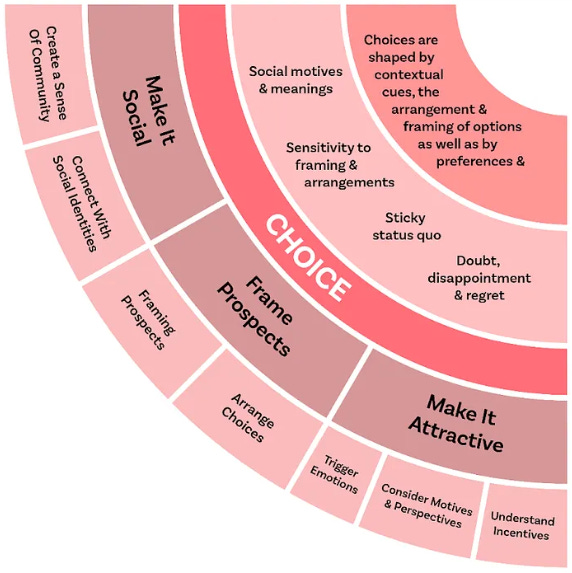

In this article, we will focus on the red section titled Choice.

Let’s dive in.

For those who would like to support this effort, you can find the entire study here for a symbolic price. It also includes examples and exercises that you won’t find in the article.

Area: Choice - Help People To Decide

The Choice area is particularly tricky because problems that appear to be matters of choice or decision-making often aren’t fully under our control. Let’s quickly summarize the aspects we’ll go over together:

Social motives and meanings

Sensitivity to framing

Adherence to the status quo

Uncertainty, disappointment, and regret

Our decisions are not entirely our own.

People often argue, “he chose to pick up the phone while driving, eat unhealthily, ignore my health app, or even join a cult and commit suicide.” But that’s only partly true. We act impulsively, influenced by stimuli or social norms.

For example, when the phone rings, we often grab it subconsciously, unaware of all the risks, because dopamine hijacks our brains. We respond automatically, without realizing it.

Choices are influenced by contextual signals, the arrangement and framing of options, as well as preferences and stimuli. Many factors affect how we decide, including social motives, sensitivity to the framing of choices, the difficulty of changing the status quo, doubts, and regret.

How can we address this area and influence decisions in a way that can help change behavior?

Here’s a summary of methods we’ll explore to influence decisions and guide behavior change:

Make It Attractive

Understand Incentives

Consider Motives & Perspectives

Trigger Emotions

Frame Prospects

Arrange Choices

Anchoring

Contrast

Golden middle choice

Framing Prospects

Make It Social

Connect With Social Identities

Create a Sense Of Community

1) Make It Attractive

Let’s start with the most obvious: Making a choice attractive is a key strategy in influencing behavior and guiding decisions. By increasing the appeal of an option, you can motivate individuals to prefer it over other alternatives.

This can be achieved in various ways, such as visual appeal, rewards, and positive associations. When an option is designed to be visually appealing, offers immediate benefits, or is associated with desirable outcomes, it becomes more attractive. Effective use of aesthetics, incentives, and emotional triggers can significantly sway decisions, making the attractive option the preferred choice.

A prime example is Apple’s design philosophy, which focuses on creating visually stunning and user-friendly products. The sleek design of iPhones, iPads, and MacBooks, combined with an intuitive interface, makes these products highly appealing to consumers.

Similarly, Tesla vehicles are designed with futuristic aesthetics and advanced features like autopilot and electric propulsion. The blend of cutting-edge technology and sleek design makes Tesla cars highly attractive to environmentally conscious and tech-savvy consumers.

Now, let’s delve deeper into all these methods—both the well-known and the lesser-known ones—in greater detail.

a) Understand Incentives

From the dawn of history, humans have always been driven by two primary forces: seeking pleasure or avoiding pain. This fundamental truth has shaped behavior throughout evolution, and it’s still the core of how we make decisions today. As you go through behaviors, at their root, it’s always about pleasure or pain.

“Show me the incentives, and I will show you the outcome.” – Charlie Munger

So, what do people really want? Only two things: to feel good or to eliminate pain. Nothing more. It’s a simple concept but not an easy task to address.

This drive has helped us survive since the time of cavemen. But here’s a question for you—can you guess which is stronger? Pain—of course. Pain is more powerful than pleasure.

If you want to use this principle in daily life, simply pause and ask yourself questions like:

What do they gain from this?

How will they benefit?

What are they definitely trying to avoid?

A simple marketing example:

Imagine two statements on a pair of running shoes:

The technology in our shoes helps you run longer.

The technology in our shoes prevents long-term ankle damage, so you can run longer.

Which would you be more likely to buy, especially if you’re not a professional runner? Probably the second one, because it addresses pain avoidance (avoiding injury) more than the first one, which focuses on pleasure.

Going deeper: Four key questions for understanding incentives

One way to start thinking about incentives is by asking four specific questions about a decision:

Who uses it?

Who chooses it?

Who pays for it?

Who benefits from it?

Let’s go through an exercise. Imagine a family—Fero and Silvia, both aged between 40-50, with two high school-aged kids, Martin and Veronika. These are some of the decisions they face:

Now, answer the four questions for each of these purchases or decisions:

Now, answer the four questions for each of these purchases or decisions:

Who uses it?

Who chooses it?

Who pays for it?

Who benefits from it?

How did you answer? If you’re like most people, you probably had different individuals for each question.

Let’s take the car as an example:

Who uses it? Mostly the mom, since she drives the kids around.

Who chooses it? Dad, with input from their son.

Who pays for it? Dad.

Who benefits from it? The whole family.

Why is this important?

It’s not enough to know the incentive itself—you also need to understand who the incentive is targeted at.

Paradoxically, as we’ve seen, many decisions that shape our lives are often made by someone else. This is critical to remember when you’re influencing behavior. Never forget that.

In my work, this framework helps me navigate conversations with management—whether with current or potential clients. You need to know who will use the product, who is responsible for it, who makes the key decisions, and which department holds the budget. Especially for big firms.

Based on this understanding, we tailor conversations—and of course, the incentives.

Remember, if you want to change people’s decisions, identify and change the incentives.

And if incentives alone aren’t enough, then there’s something even stronger: people’s motives and perspectives. We’ll dive into that next.

b) Consider Motives & Perspectives

Even though the title of my blog wasn’t originally based on this method, the name “Why and Actually How” largely addresses it.

Before we dive into motives, let’s first discuss the importance of perspectives, best explained by the phenomenon of selective perception.

Selective perception is a form of bias that causes people to interpret messages and actions according to their own frame of reference. It leads individuals to overlook or forget information that contradicts their beliefs or expectations. In other words, people see in media what they want to see and ignore opposing views.

For example, if you’re a smoker and a huge football fan, you’ll likely ignore negative ads about smoking because you already smoke and believe it’s okay. But if an ad about football appears, you’re more likely to notice it because you have a positive view of football. This demonstrates how we perceive the world through our subconscious filters, selectively absorbing what aligns with our interests.

This is where sayings like “seeing the world through pink glasses” come from. It’s a broad term describing how people tend to “see things” based on their unique reference points. It also explains how we categorize and interpret sensory information in a way that favors one interpretation over another. In other words, selective perception is a form of bias because we interpret information in line with our existing values and beliefs.

Psychologists believe this process happens automatically.

Anytime someone makes a decision, two questions instantly come to mind:

Why are they doing it? (Motives)

What frame of reference are they coming from? (Perspective/Perception)

So, always try to understand the perspective of the person.

The first question—“Why are they doing it?”—basically addresses their motives. From behavioral economics, we know a well-known tendency that directly relates to this topic, known as the Reason-Respecting Tendency.

Before we act, we want to know why. That’s why, when delegating tasks to others, you should always share why the task is important.

You can get people to act in their best interest if you give them a reason, even if the reason is sometimes trivial.

Simply put, you can increase agreement with a request, favor, or command if you provide a reason.

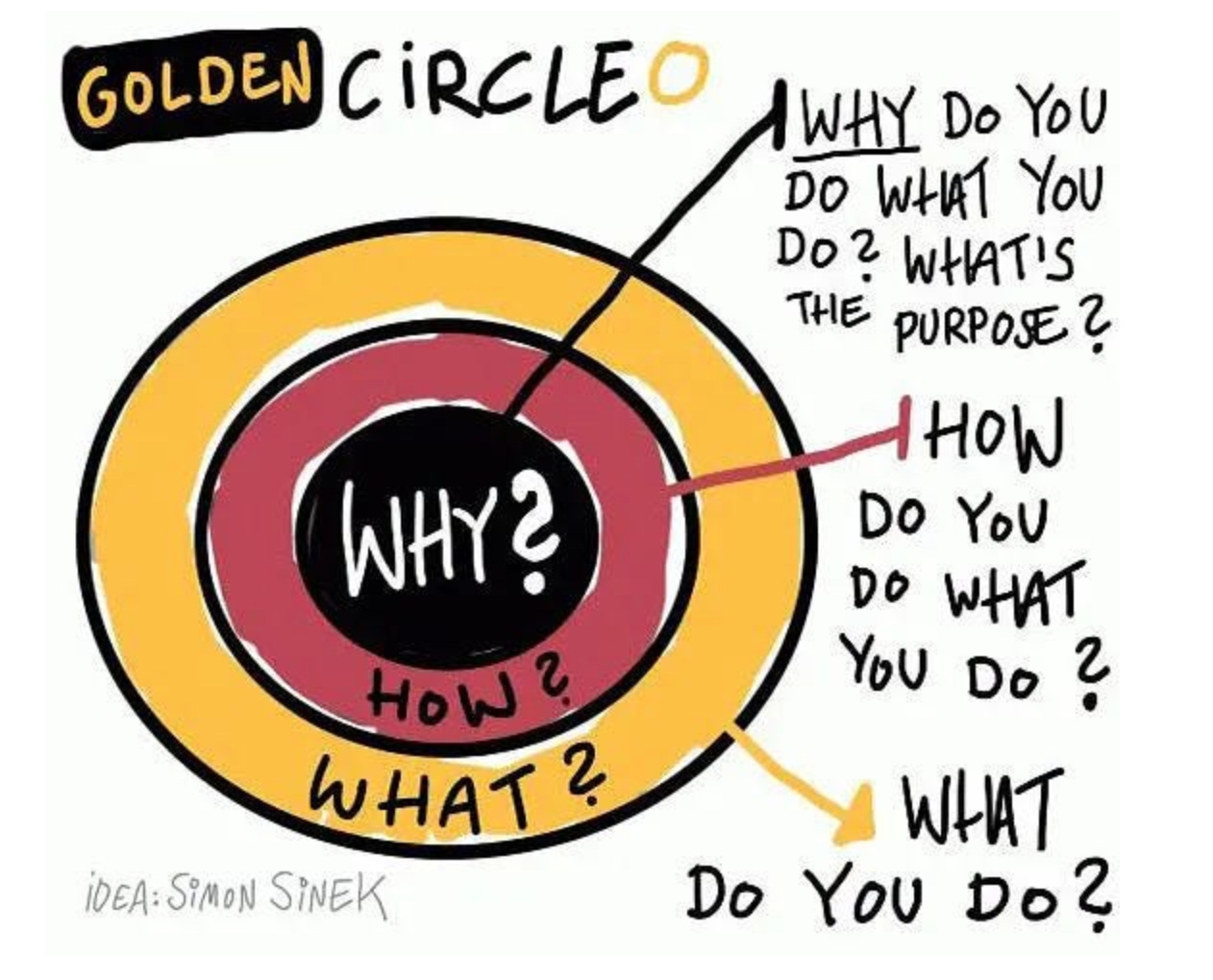

Simon Sinek, in his book and a famous TED Talk, codified what others do wrong and how the best win by starting with Why—which sits right at the center of his famous Golden Circle.

This reinforces the idea that understanding human motives is not just important but crucial. Even in criminal cases, judges seek motives behind the crime and use this “subjective” factor to determine the severity of the punishment.

For instance:

Imagine you’ve killed someone, and you’re in front of a judge. The judge asks, “Why did you do it? What was your motive?” Here are two different responses:

“The man tried to rape me, so I grabbed the nearest object and hit him. He died.”

“Because there’s nothing more beautiful than the sound of a dying person’s scream.”

Who do you think will receive a harsher punishment?

I know it’s an extreme example, but it illustrates how important motives are.

So, if you’re trying to change a decision, ask yourself this simple question repeatedly:

Why would people do it?

Why should they buy, use, or offer it?

You’d be surprised how many people give surface-level answers like, “because it’s healthy, useful, cheaper, or better than the competition.”

These are not sufficient reasons. Dig deeper to understand their true motives and address them directly.

Wanting to be healthy is a good motive, but wanting to be healthy enough to travel to places you’ve always wanted to visit or to play with your future children is a much stronger one.

Once you understand the motives, your next task should be to trigger emotions.

c) Trigger Emotions

Emotions play a crucial role in decision-making, often influencing choices even more than logical reasoning. By triggering specific emotions, you can effectively steer behavior and decisions.

For instance:

Positive emotions like joy and hope can encourage people to take actions that align with these feelings, such as trying new things or embracing changes.

Negative emotions like fear or guilt can push individuals to make decisions aimed at avoiding threats or correcting mistakes.

There are various ways to trigger emotions, including storytelling, imagery, or evocative language. Using emotional triggers effectively requires a deep understanding of the experiences and cultural background of your target audience. Shaping your messages to touch on emotional chords that resonate with your audience can profoundly influence their decision-making process.

Remember, the most effective emotional triggers are those that feel authentic and create a sense of connection and relevance.

A Fun Example:

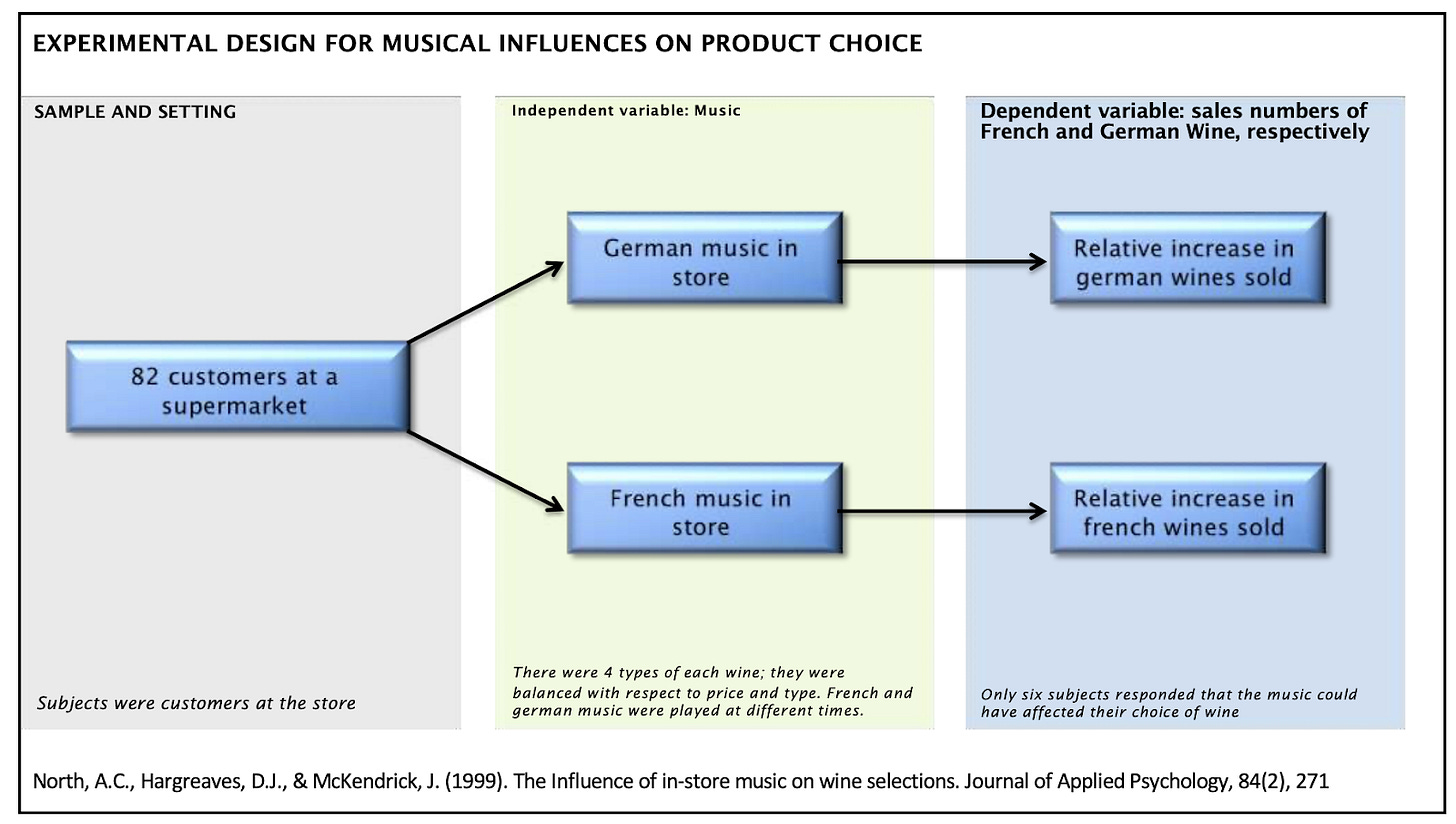

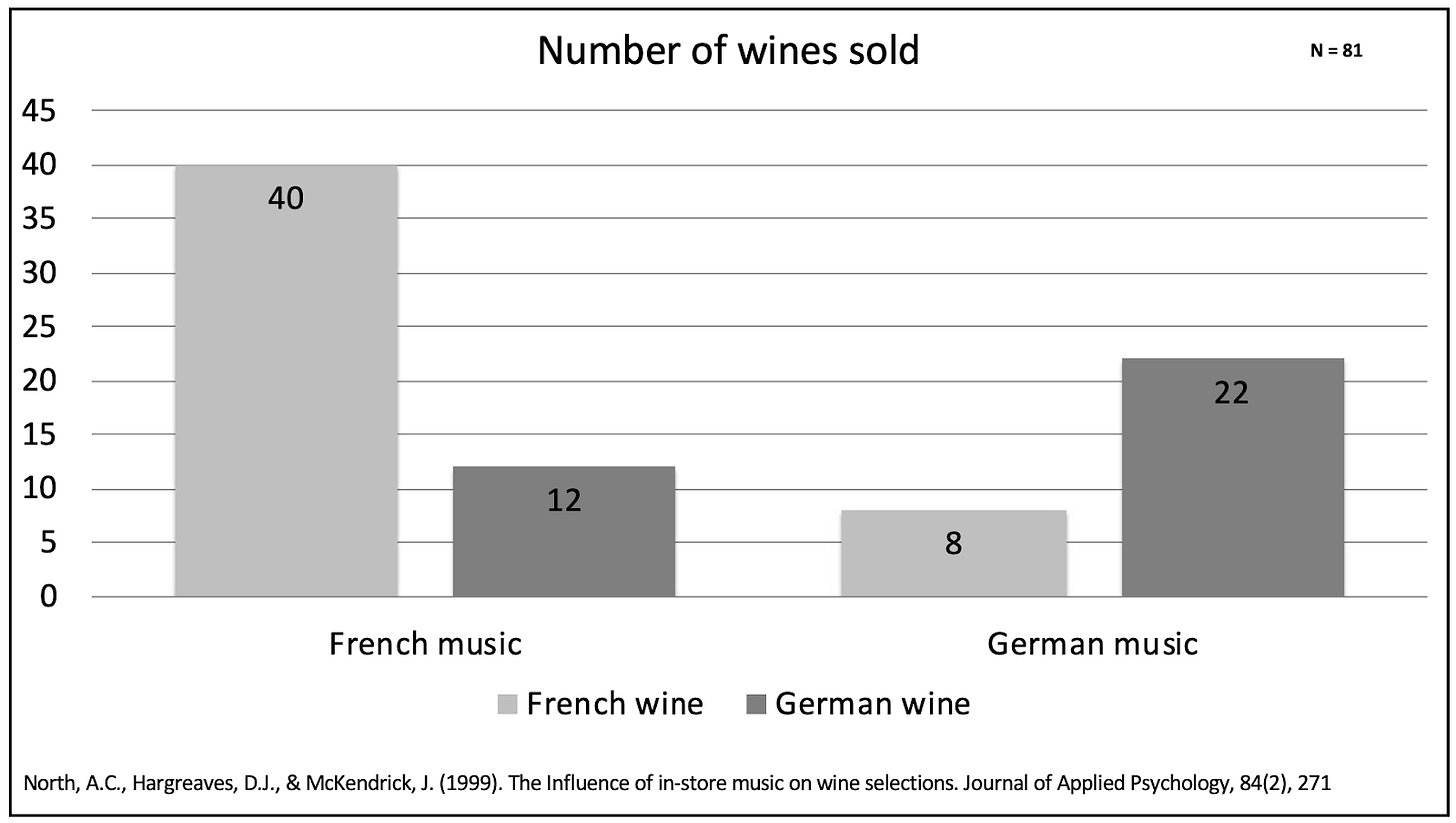

In a fascinating experiment published in the Journal of Applied Psychology, researchers tested whether the music playing in a wine shop would influence the type of wine customers bought. The assumptions were:

When French music played, customers would be more inclined to purchase French wine.

When German music played, customers would be more inclined to buy German wine.

And this was the result:

Sure enough, the results supported this assumption: the music significantly affected wine choices! This experiment shows how subtle emotional triggers like background music can shape purchasing behavior.

It’s similar to why supermarkets place commonly bought items like alcohol or bread at the far end of the store. The idea is that customers walk through the entire store, increasing the chance that something else will catch their eye and prompt them to buy.

Now, let’s take a look at emotional influence from another angle—through the lens of my favorite cognitive biases and tendencies.

i) Indentifiable Victim Efect

This phenomenon, known as the Identifiable Victim Effect, occurs when individuals are more emotionally impacted by the problems and struggles of a single, identifiable person than by a large, anonymous group facing the same or even worse problems. It’s a powerful cognitive bias frequently used in advertising, marketing, sales, and any form of communication to evoke emotional responses.

As Joseph Stalin famously said, “A single death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic.”

This bias highlights how people tend to feel more connected and emotionally moved by a personal story rather than overwhelming numbers or data.

Let’s look at real-life examples to demonstrate how this works and why it’s so effective:

Which image stirs more emotion?

Imagine being presented with two images:

A large crowd of people suffering from hunger.

A close-up image of a malnourished child with a direct appeal for help.

or

Most people will feel more emotionally affected by the second image, where the personal story is visually and emotionally more relatable.

Another example:

or

Which one is more likely to evoke a stronger emotional response?

Why does this happen?

This bias is deeply rooted in our psychology. We naturally relate to individual stories because they make the issue tangible and personal. When the human mind is faced with statistics or large groups, it struggles to process the emotional depth of the situation, and people feel disconnected.

This is why yearly award-winning photographs often feature individuals or small groups that tell a powerful story through a single image. These images resonate deeply because they reflect personal experiences, which we instinctively empathize with.

How can this be used in the real world?

Here are a couple of ways organizations utilize the Identifiable Victim Effect:

GoFundMe: Crowdfunding campaigns on platforms like GoFundMe often highlight individual stories with specific needs. Medical campaigns, for example, frequently showcase a single patient’s journey, including photos and personal updates. This creates an emotional connection that motivates donors.

World Wildlife Fund (WWF): WWF’s adoption program allows donors to “adopt” a specific animal, like a panda or tiger. Donors receive photos and details about their adopted animal, making the donation feel personal and emotionally significant.

Key Takeaway:

To effectively influence behavior and evoke emotions, focus on personalizing your message. Highlight individual stories or experiences to tap into the power of human empathy. Whether you’re raising funds, marketing a product, or advocating for a cause, the more relatable and human the story, the stronger the emotional impact.

2) Frame Prospects

Framing Prospects is a powerful tool, influencing how people perceive life, and it’s something I use in everything I do.

There’s no such thing as an “objective” reality—it’s always about how you choose to frame or view things from a certain perspective.

To make this concept clearer, let’s look at a simple example. When I analyze a product, service, or business to identify and manage risks, I also focus on how it’s presented. Depending on the size of the company, the same service can be framed differently:

Small company? “You’ll receive top-notch personal service tailored to your needs.”

Medium-sized company? “We can efficiently cover most of your needs with speed.”

Large company? “We offer tried-and-tested methods refined over years with hundreds of clients.”

It’s the same product or service, but the framing of it shifts depending on the target. That’s the power of framing—it’s about leveraging your strengths effectively.

Now, let’s dive into some techniques you can use for better framing:

a) Arrange Choices (Usporiadajte Výbery)

The way you arrange options or present choices is key. Some people feel uneasy about using these techniques, thinking they don’t want to influence choices or manipulate people.

However, not doing anything is also a choice. Everything we do influences or guides a decision. Even by not presenting options, you’re nudging people not to make a choice or purchase.

Here are three techniques from the behavioral space that are incredibly effective in framing choices:

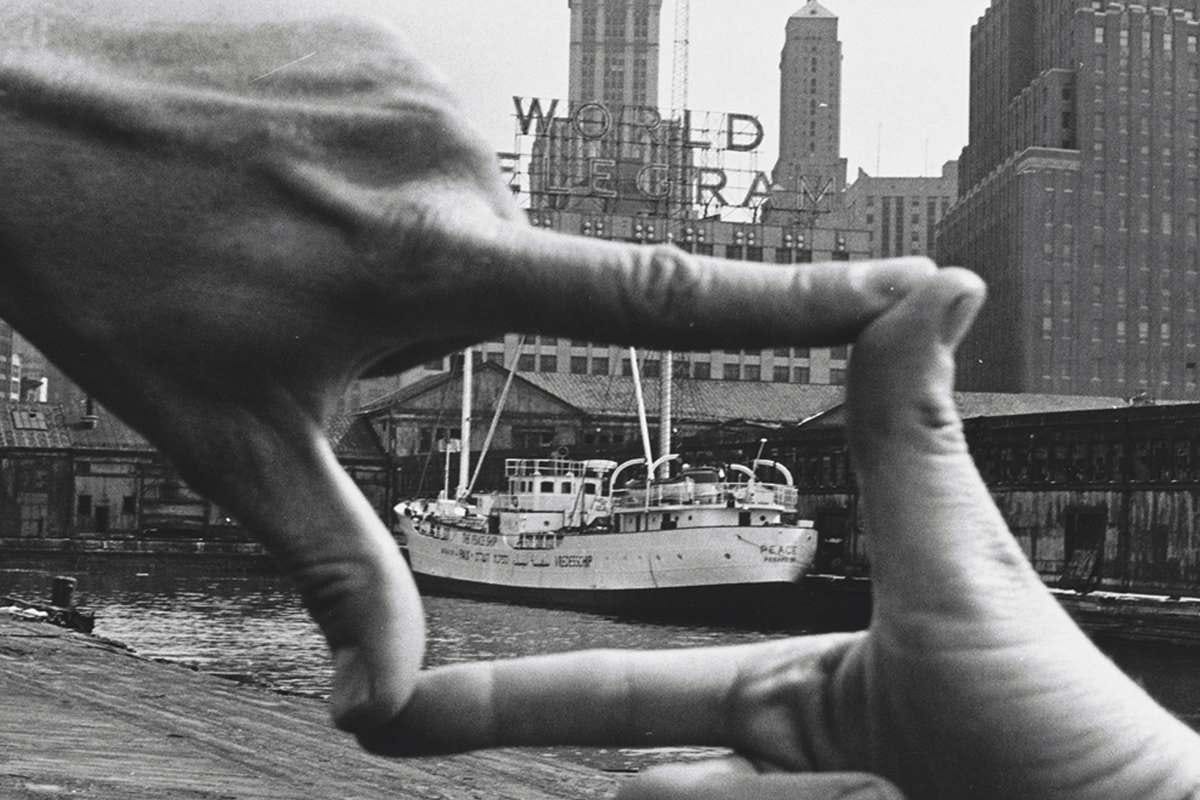

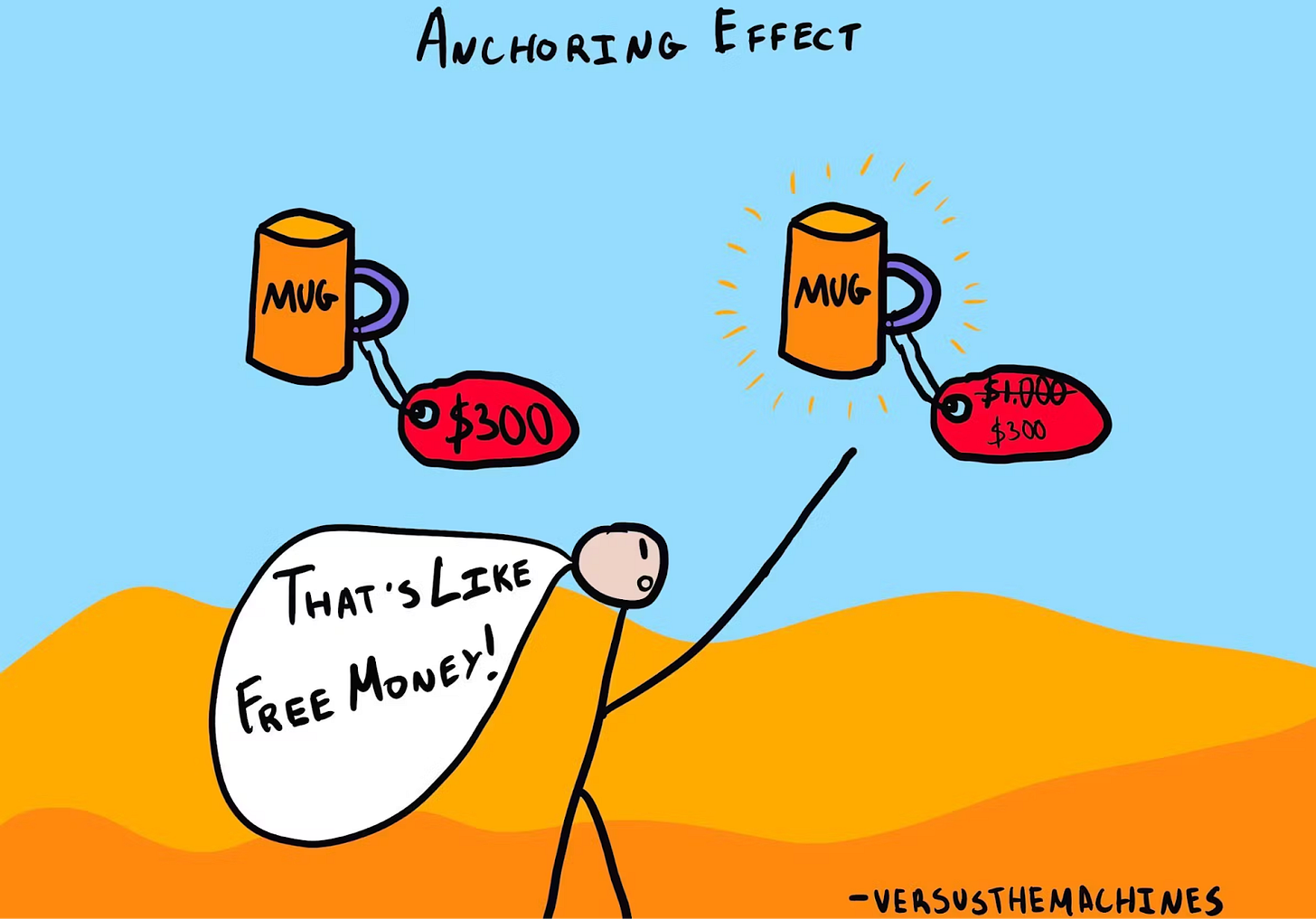

Anchoring

Definition: This involves giving people a reference point (anchor) to base their decisions around. It’s why sale prices always show the original, higher price next to the discounted one.

Example: When people see a pair of shoes marked down from $200 to $120, they’ll feel like they’re getting a bargain, even if the shoes’ real value is closer to $120.

Contrast

Definition: Highlighting differences between options can make one option seem more appealing in comparison.

Example: A luxury car dealership may show a basic model alongside a fully loaded one to make the upgraded model seem like a better deal, even though it’s more expensive. The basic model is there to provide contrast and push people toward the pricier option.

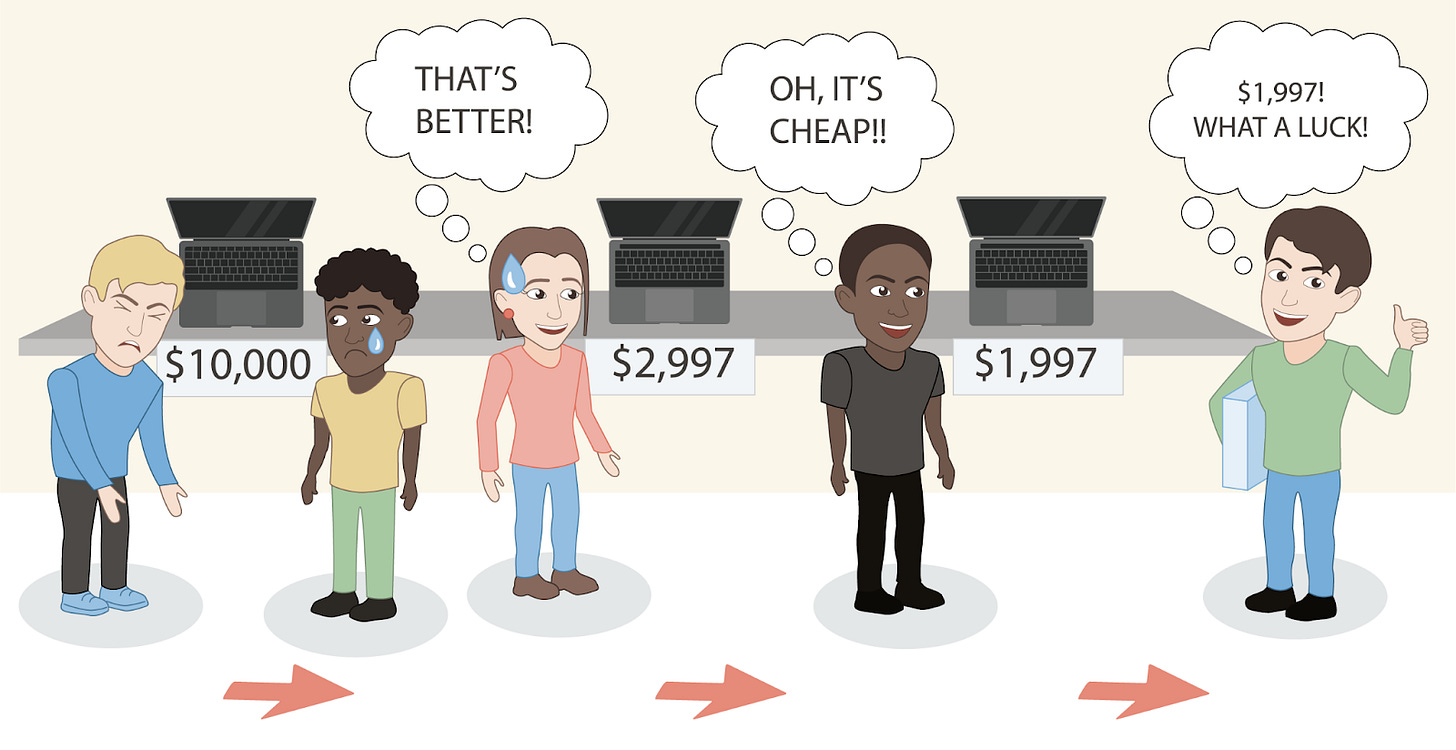

The Golden Middle (Compromise Effect)

Definition: When given three options—low, medium, and high—people tend to go for the middle one, as it feels like the “safe” choice.

Example: If you’re selling software subscriptions, offering a basic plan at $20, a premium plan at $50, and an elite plan at $100, most users will gravitate toward the premium plan, viewing it as the “safe middle ground.”

Ladders (Bonus)

Definition: This technique involves providing a sequence of progressively higher-value options that guide customers toward upgrading.

Example: Start with a basic service, but show users how they can improve their experience by adding features or moving up to a more comprehensive package—essentially guiding them up a ladder of value.

i) Achoring

People typically rely on the first pieces of information they receive—regardless of how reliable those pieces of information are—when making decisions. The first bit of information has a huge impact on our brain.

For example, if you’re asking someone to guess how tall something is, and you suggest whether it’s higher or lower than 1,200 meters, you’ll influence their judgment more than if you let them guess without any context.

You can try this for yourself. Researchers conducted a simple experiment where they asked people two questions: “How happy are you these days?” and “How many dates have you been on in the past month?” For one group, they first asked how happy they were, and for the other group, they asked how many dates they had been on first.

In the group where they asked about the dates first, the correlation between happiness and the number of dates was as psychologically strong as it could get.

If you want to see a masterclass in anchoring in real life, check out a video where Steve Jobs presents the pricing for Apple products.

Having high-priced main dishes on a menu increases a restaurant’s revenue—even if no one orders them. Why? Because even though people usually don’t buy the most expensive dish on the menu, they tend to order the second most expensive one. By having a pricey option available, the restaurant can entice customers to order the second-highest-priced dish (which might be cleverly designed to have a higher profit margin).

The anchoring effect isn’t just a laboratory curiosity; it can be just as powerful in the real world. In an experiment conducted several years ago, real estate agents were asked to assess the value of a house that was actually on the market. They visited the house and studied a comprehensive brochure of information, which included an initial price. Half of the agents saw an initial price significantly higher than the listed price; the other half saw an initial price significantly lower. Each agent then gave their opinion on the reasonable purchase price of the house and the lowest price at which they would be willing to sell the house if they owned it. Afterward, the agents were asked what factors influenced their judgment. Remarkably, the initial price was not one of the factors they mentioned; the agents were proud of their ability to ignore it. They insisted that the initial price had no influence on their answers, but they were wrong: the anchoring effect was 41%. In fact, the professionals were almost as susceptible to anchoring effects as business school students with no real estate experience, whose anchoring index was 48%. The only difference between the two groups was that the students admitted to being influenced by the anchor, while the professionals denied it.

Now, let’s move on to the next point.

ii) Contrast

People tend to make decisions based on comparisons rather than evaluating each situation on its own.

Take today’s world, for example. Most people in first-world countries live better than any king from hundreds of years ago, in terms of the technology they own and the comforts they enjoy at home. But are we happier? Not really, because we evaluate things relative to other things rather than measuring them in absolute terms.

You could argue that this is how the entire world operates—especially markets and economies. Value is derived by comparing something to something else or by creating categories. Both of these methods can be quite dangerous and misleading.

This is why it’s so easy for someone to add $200 to a $5,000 catering bill for soup, while that same person will clip coupons to save 25 cents on a can of condensed soup that costs $1.

Similarly, it’s easy for us to justify spending $3,000 on leather seat upgrades when buying a new $25,000 car, but it’s much harder to spend the same amount on a leather couch (even though we know we spend more time on the couch at home than in the car).

Bentley figured this out and stopped going to normal car shows, because then the car is too expensive, and started showing at yacht or private plane shows. Because when you looking at multi-million dollar planes or yachts, 300k car looks like a bargain now.

The same principle applies to how we perceive value. We don’t measure the value of things in a vacuum. Instead, we often notice value by comparing it to something else. Retailers take advantage of this by setting an artificially high price for their product and then offering a deep discount.

Want to make a house seem large? Compare it to a smaller house next door.

Here’s a fun tip if you want to annoy someone when they ask you to estimate anything: say a wildly exaggerated number in a serious voice. This hilarious video at the start illustrates this idea perfectly.

iii) Golden Middle Choice (Compromise effect)

I talked about these choices, including the “golden middle choice” concept, and showed a real-life example in a case study from one of the most successful e-commerce companies.

The compromise effect, also known as the tendency towards the middle option, refers to the consumer’s preference for the middle choice among a set of options. This happens because the middle choice is often perceived as the safe, moderate option that avoids the extremes of the cheapest or most expensive alternatives. By strategically positioning products or services, businesses can influence consumer decisions and boost sales.

Understanding the compromise effect can help in designing product offerings that cater to this natural tendency, leading customers to make more balanced decisions.

Digital Products:

Subscription plans for streaming services (e.g., Netflix): Netflix offers several subscription tiers (Basic, Standard, Premium). The Standard plan, often positioned as the middle option, is the most popular because it strikes a balance between features and price, appealing to users who want more than the basic service but find the premium option too expensive.

Software subscription models (e.g., Adobe Creative Cloud): Adobe Creative Cloud offers multiple pricing tiers for its software. The middle option, which usually includes the most essential tools, is often the most popular because it effectively balances cost and functionality.

Physical Products:

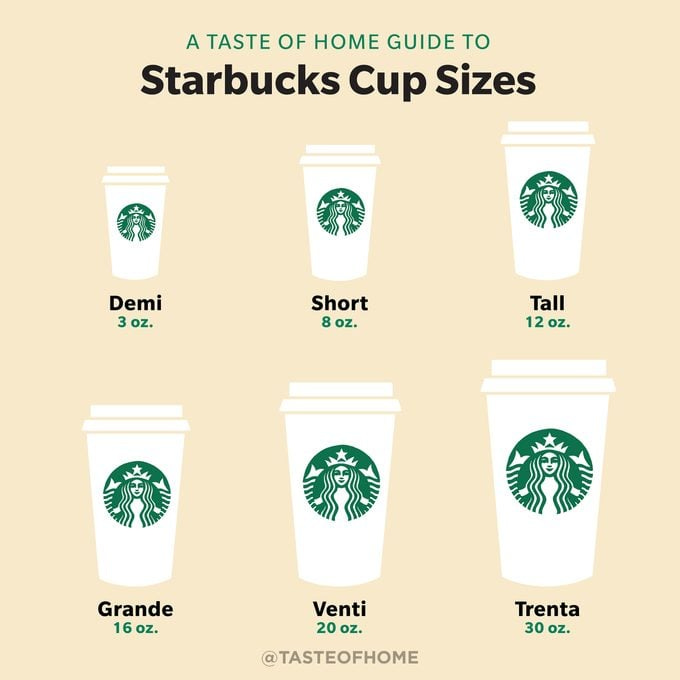

Coffee sizes (e.g., Starbucks): Starbucks offers coffee in three sizes (Tall, Grande, Venti). The Grande size, being the middle option, is often the most selected by customers because it is perceived as the most reasonable amount—not too small, not overly large.

Car models (e.g., Toyota): Car manufacturers like Toyota offer their vehicles in several trim levels (Base, Mid-range, Premium). The mid-range trim, which typically includes basic features at a reasonable price, is usually the best-seller because it balances affordability and appeal.

Sometimes, like with the XXXL popcorn at movie theaters or Venti or Trenta sizes at Starbucks, the largest option is there merely to push customers toward buying the next largest option (in this case, Grande). It’s often obvious when the largest version is so enormous that almost no one would actually order it.

iii) Ladders

The Power of Ladders: Guiding Customers to Upgrade

The ladder technique is a powerful strategy used in sales, marketing, and product design to guide customers through a series of progressively higher-value options, ultimately encouraging them to upgrade.

Imagine it like climbing a ladder—each rung offers more benefits, features, or value, prompting customers to see the next step as a natural progression. By showing incremental improvements, you give customers the sense that upgrading is the right choice for maximizing their experience.

Here’s how it works:

Start with a Base Option

At the bottom rung, you offer a basic product or service. It’s affordable and provides the essential features a customer needs. However, it subtly hints that more value is available if they go higher.

Introduce the Upgrade

As customers experience your base option, present the next step up the ladder—a premium version with additional features or better functionality. Because they’re already invested in the first level, the perceived value of upgrading becomes more attractive.

Highlight Benefits

Make it clear what customers gain by moving up. More convenience, greater efficiency, or added perks? Show them how each step adds significant value, making the higher tier seem like the smarter investment.

Guide them to the Top

At the top, your elite offering awaits. This is the version for those who want the full package and are willing to pay for it. You’ve guided them through each step of the journey, making it easy for them to see why upgrading to the best option is a natural conclusion.

Example in Action:

A SaaS company might offer three pricing tiers:

Basic Plan ($20/month): Core features.

Premium Plan ($50/month): Core features + analytics and integrations.

Elite Plan ($100/month): Everything in Premium + dedicated support and custom features.

The basic plan hooks users in, but the additional benefits of the premium and elite plans entice them to move up the ladder for greater value.

Why It Works:

The ladder approach taps into human psychology, making upgrades feel like a logical progression rather than a splurge. Customers are already invested, so moving to the next level feels like they’re enhancing their initial choice.

By structuring your offerings as a ladder, you maximize customer engagement and increase revenue through strategic upselling—while keeping the customer feeling satisfied and in control.

How Apple Organizes Phone Choices

Apple creates what can be called “ladders,” where you start with a basic product that is perfectly sufficient for over 90% of people. It’s probably the one you should choose. But if you look just a little further, you’ll find a model that’s slightly shinier and a bit more expensive.

For instance, let’s look at the iPad lineup. You have the base model for $330, which is great for most users. But then there’s a $450 model that has a sleeker design, USB-C, a better display, and is slightly larger, making you think, “I could get that one instead.”

However, this model only comes with 64GB of storage, so you might consider the version with more storage, which costs $599. But wait, the iPad Air is also $599. So, naturally, you think, “Maybe I should just get the iPad Air,” but now the iPad Air also comes with limited storage, and you can see where this is heading.

Essentially, Apple gently guides you up the ladder, from one product to the next, encouraging you to keep upgrading.

This strategy is how I ended up buying the most expensive Samsung at the time, the Samsung Galaxy S22 Ultra.

b) Framing Prospects

The framing effect is a type of cognitive bias where people respond differently to the same choice depending on how it is presented—either as a loss or a gain.

When presented with a positive frame, people tend to avoid risks, but when presented with a negative frame, they are more likely to take risks. The definitions of gain and loss come from how outcomes are described (e.g., number of lives saved or lost, patients treated or untreated, lives saved or lost during accidents, etc.).

It’s not about what you say, but how you say it.

Who is right? Both

For example, in a study by Levin and Gaeth (1988), participants enjoyed beef more when it was described as “75% lean” compared to “25% fat.”

Similarly, when people were shown two kinds of milk—one labeled “99% fat-free” and the other “1% fat”—they chose the first one as healthier. Even when presented with milk that was “97% fat-free” and “1% fat,” most still chose the first option, despite it having more fat. This illustrates how subtle wording can impact perception, a common form of framing.

In marketing and everyday communication, the framing effect is everywhere. Declining stock prices are called “market corrections,” and overpaying for a company is labeled as “goodwill.” A “problem” in business becomes a “challenge,” and a person getting fired is “re-evaluating their career” or “spending more time with family.”

One classic example involves the way risk is communicated: imagine reading that a “vaccine that protects children from a deadly disease carries a 0.001% risk of permanent disability.” That seems small, right? Now consider this: “1 in 100,000 vaccinated children will be permanently disabled.” The second statement makes the risk feel more real, evoking an image of that one child who might be affected, while the 999,999 children who are safely vaccinated fade into the background.

So, what can you do? When framing a message, write down all the different ways you can present the same information from various perspectives. Are there alternate ways you can propose, suggest, or implement an intervention?

By exploring different frames, you can influence how people interpret your message, whether in business, marketing, or everyday conversations.

3) Make It Social

Leveraging Peer Influence in the Digital World

The concept of making choices social isn’t new, but it’s more relevant than ever in today’s connected world.

As social creatures, our behaviors and decisions are often influenced by what others around us are doing. Incorporating social behavior in digital environments is a powerful way to guide actions and decisions. I’ve detailed this concept in my case study analyzing Amazon, and here’s a look at how this can be applied more broadly.

Why Make Choices Social?

By leveraging social proof and peer dynamics, you can make certain behaviors more attractive. When people see their peers engaging in specific activities, they are more likely to follow suit. This is due to a natural desire to fit in and seek social validation.

How can this be implemented in the digital world? By integrating social elements into the decision-making process, such as showcasing what others are doing or encouraging social sharing, organizations can nudge users toward desired behaviors. This approach taps into our human need for connection and recognition, making it more likely that people will adopt new behaviors.

Here are a couple of examples:

Strava

Strava, the fitness app, has mastered the use of social influence by allowing users to share their workouts, follow friends, and participate in challenges. By seeing their friends’ activities and achievements, users are more motivated to stay active and reach their fitness goals.

Coca-Cola’s “Share a Coke” Campaign

Coca-Cola’s iconic campaign personalized bottles with people’s names, encouraging customers to find bottles with their friends’ names and share pictures on social media. This campaign brilliantly tapped into social connections to boost sales and engagement, making the product more personal and shareable.

Source: https://thebrandhopper.com/2023/06/09/branding-case-study-success-of-share-a-coke-campaign/

Incorporating social proof into your product or marketing strategy can significantly increase engagement by aligning with one of the strongest human motivators—the desire to connect with others.

a) Connect With Social Identities

Linking choices to social identities is a highly effective strategy for influencing decisions and behaviors. People often make decisions that align with the communities they identify with, whether those are cultural, social, or professional groups. By understanding and appealing to these social identities, you can create messaging and interventions that deeply resonate with your target audience.

For example, when promoting a new product, framing it in a way that emphasizes how it aligns with the values and norms of a specific community can significantly increase its appeal.

This approach leverages the innate human desire to belong and be accepted, making it more likely that individuals will adopt behaviors that reflect their social identity. Effective use of this strategy requires empathy and thorough research into your target group to ensure that your messaging feels authentic and relevant.

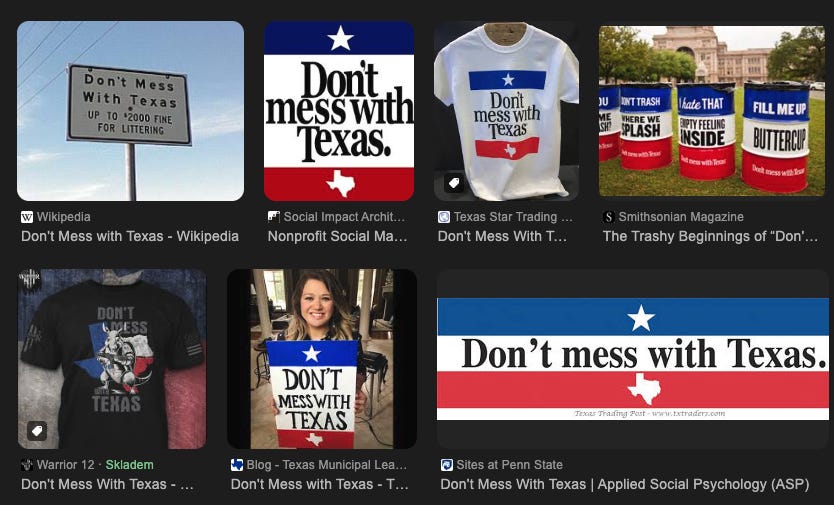

A well-known case study that exemplifies this approach is the “Don’t Mess with Texas” campaign, a public service advertising effort that successfully tackled the state’s littering problem. Let’s dive into the key elements of this campaign:

Overview of the “Don’t Mess with Texas” Campaign

Background:

In the mid-1980s, Texas was facing a serious littering problem, costing the state around $20 million annually to clean up roadside trash. The Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) needed a highly effective strategy to curb littering.

The Campaign:

Slogan: The now-iconic slogan, “Don’t Mess with Texas,” was created by the advertising agency GSD&M in 1985. It aimed to tap into Texas pride with a strong, almost rebellious message against littering.

Target Audience: The primary target group was young men aged 16-34, who were identified as the most frequent litterers. The slogan was crafted to resonate with this group by appealing to their sense of state pride and masculinity.

Execution: The campaign included a series of TV commercials, radio spots, and print ads featuring famous Texans, such as musicians Willie Nelson and actors like Chuck Norris. These ads portrayed littering as un-Texan and emphasized personal responsibility for keeping Texas clean.

Cultural Impact: The slogan quickly became a cultural phenomenon, embraced by Texans and widely recognized. It appeared on bumper stickers, t-shirts, and other promotional items, helping to further spread the message.

Results: The campaign was highly successful:

Within the first few years, roadside littering dropped by about 72%.

The slogan became synonymous with Texas pride and environmental responsibility.

The campaign won numerous awards and is often cited as one of the most successful anti-littering campaigns in history.

Key Takeaways

Cultural Resonance: The success of the campaign highlights the importance of understanding and leveraging local culture and values in public service messaging.

Clear and Memorable Messaging: The slogan was simple, catchy, and easy to remember, which made it extremely effective.

Influential Figures: Featuring respected public figures helped legitimize the message and influence behavior.

Targeted Approach: Identifying and specifically addressing the primary demographic of litterers made the campaign more focused and impactful.

This case study illustrates how strategic messaging, rooted in cultural understanding, can effectively change public behavior and tackle societal issues.

b) Create a Sense Of Community

When individuals feel like they are part of a community, they are more willing to engage in activities that benefit the group and align with its norms and values.

This sense of belonging fosters loyalty, collaboration, and a willingness to support the community’s initiatives. To cultivate a sense of community, encourage interaction and connection among members through events, forums, or shared activities.

Emphasize common goals and celebrate collective achievements to strengthen mutual bonds. By building a strong community, you create an environment where positive behaviors are encouraged and sustained, leading to more cohesive and motivated groups.

Facebook communities have been around for years and are one of the best ways to drive sales for businesses that manage to build and maintain these groups. Nowhere will you find more loyal customers. Various community-driven approaches have become popular in recent years. One example is crowdfunding platforms like Crowdberry or community-driven investment platforms for charitable projects like Donio.

I even wrote a case study on this type of investment, where I reflected on why I believe the startup Take Up failed to raise any money despite being a social app.

Another exciting project that has caught my interest is Skool, a platform that gained attention after a major investment from one of my favorite YouTubers and entrepreneurs, Alex Hormozi, who now promotes it everywhere.

Skool is an educational platform that combines online courses, community discussions, and interactions to enhance learning experiences. The platform focuses on creating an engaged and supportive community where participants can motivate each other, share their knowledge, and grow together. It’s designed to facilitate learning and development across various areas, from professional skills to personal growth.

Communities centered around small, shared interests are one of the strongest assets in business and a fantastic way to start.

If the way I approach things resonates — or if your product, idea, or strategy feels even slightly “off” — I might be able to help.

Let’s have a quick 20-minute call to find clarity together:

Final Words

We’ve reached the end of the section on decision-making. I hope you now understand why your decisions aren’t truly your own.

In the next article, we’ll move on to the next topic, Determination, which includes some of my favorite (and highly underrated) methods for influencing human behavior, motivation, and determination.

See you in the next article.

- Peter

For those of you who want to explore the previous sections:

[1/6] Introduction to the ABCD Framework

For those who would like to support this effort, you can find the entire study here for a symbolic price. It also includes examples and exercises that you won’t find in the article.