[5/6] Ultimate Guide: Model for Identifying and Changing Behavior - Determination

In today’s fast-paced world, where everyone demands something from us, energy is precious, and determination is often directly linked to it. Learn how to effectively manage energy & determination.

Welcome to the fifth part of our series where we explore the ABCD Framework, either as a whole or in individual parts.

For those of you who want to explore the previous sections:

[1/6] Introduction to the ABCD Framework

In the previous article, we focused on the area of Choices. It was one of my favorite topics and certainly one of the key areas. We explored how to identify human decisions, understand them, and then work with them. Now, we will dive deeper into a field that people often confuse with choices, because our determination is difficult to measure, and for that reason, most behaviors in this area are labeled as ‘choices.

Just as a reminder, here’s the full model:

In this article, we will focus on the yellow section titled Determination.

Let’s dive in.

For those who would like to support this effort, you can find the entire study here for a symbolic price. It also includes examples and exercises that you won’t find in the article.

Area: Determination - Help People Overcome Own Biology

The fourth area is Determination. The strength of our willpower is a limited resource that can easily be depleted. The less energy we have, the weaker our willpower becomes, and in turn, the less likely we are to engage in complex decision-making

People often think we have unlimited willpower, but they couldn’t be more wrong. Willpower is a finite resource that can be drained quickly, and it also requires certain competencies to be effectively utilized.

Some factors that drain our determination include:

Self-blame

Cognitive dissonance

Mental fatigue from previous actions

Inability to make decisions

Procrastination

Imagine willpower like a battery, with every decision you make depleting a bit of that energy. As you continue, the reserve gets lower and lower.

Imagine willpower like a battery, with every decision you make depleting a bit of that energy. As you continue, the reserve gets lower and lower.

Even worse, the less willpower (determination) you have, the worse your decisions become, or the longer it takes you to do something.

Willpower is a precious resource, and we need to understand how to manage it. But it’s not just about managing our own willpower; we should be creating solutions that take into account this limitation—either directly or indirectly.

In this section, we’ll explore areas such as:

Make It Easy

Default Effect By Cognitive Avoidance

Work With Friction

Perceived effort

Indirect Communication (Nepriama Komunikácia)

Implement Intentions

Feedback

Psychology of Waiting

Operational Transparency

Create Social Expectations

Create Commitments

Leverage Social Norms

1) Make It Easy

Make it simple – it sounds like a total no-brainer, to the point where you might wonder why I’m even mentioning it. But some sections don’t need revolutionary insights; instead, they serve as reminders to pause, reflect, and ensure you’ve addressed the basics properly. I’m also here to share a few methods on how to address simplicity.

People love to overcomplicate things, myself included, because it subconsciously makes us feel like we’re doing something more impressive, or it feeds our egos. For others, overcomplicating things can be a sign they don’t fully understand the subject, so they dress it up in complexity.

“If you can’t explain it simply, you don’t understand it well enough.” – Albert Einstein

You really learn this lesson when you work in client-based businesses, where everything you do needs to be presented simply to your clients.

Here’s a short example: We recently built a simple app, and I created a straightforward customer flow.

Of course, when you’re on alignment calls with clients, you have to translate things into even simpler designs and be ready with a clear, easy-to-follow story.

So when I joined the client call, I was prepared like this:

Even such simple interventions, where you simplify things for the client, translate into other areas of work, and you start applying them everywhere.

A lot of people don’t do this because it involves doing double the work – breaking down what you already did into simpler forms – but that’s the reality of working in services or consulting.

Now, let’s dive into some key insights and methods that will help you create simple, effective solutions.

a) Default Effect By Cognitive Avoidance

The default effect due to cognitive avoidance refers to the phenomenon where individuals tend to stick with preset options or preferences because of the mental effort required to make an active decision. This effect leverages the human tendency to avoid complex decision-making processes, often leading people to accept defaults as the path of least resistance.

By strategically setting advantageous default options, you can guide behavior in a desired direction with minimal effort on the user’s part. This technique is widely used in both digital and physical products to influence user decisions and enhance user experience.

Many people will choose whichever option requires the least effort, or the “path of least resistance.”

It works not only with default options but also with recommended options. Let’s explore this with an example involving organ donation.

Here’s a chart displaying the percentage of people in different countries who donate their organs posthumously:

The difference isn’t in culture, geopolitics, or various campaigns. The difference lies in the simple fact that in the blue countries, if you receive a letter and don’t check the box, you are automatically enrolled in the organ donation program. Conversely, in the red countries, you are not enrolled unless you actively check the box.

This is a beautiful way to use this method to save many lives.

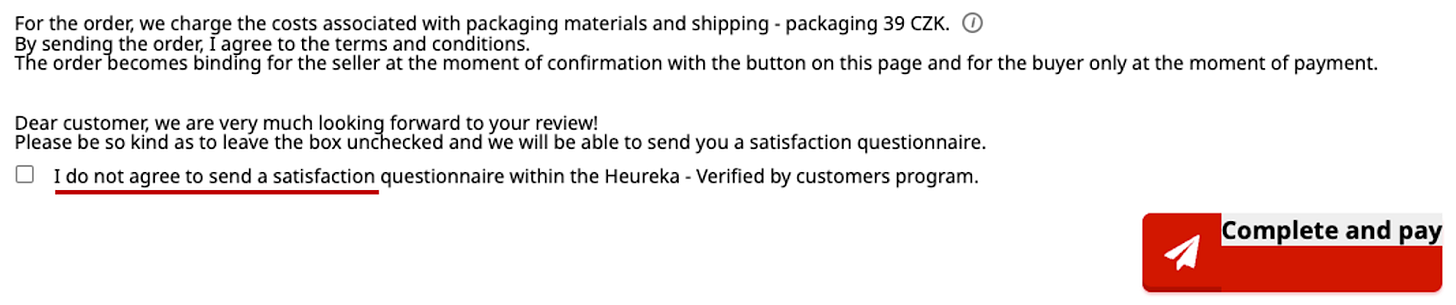

However, many companies, especially in e-commerce, started using this method for marketing purposes. For instance, if you don’t want to receive a survey, you have to explicitly uncheck a box. Since most actions on the page involve clicking to say “yes” to things, these advertising interventions deliberately reverse the logic.

Of course, I advocate for ethical interventions and dislike when people are “manipulated” into a specific decision.

So, how can you apply this method in a way that feels unobtrusive yet still offers a sense of free choice?

Give users a clear choice upfront between “regular (recommended)” and “custom” options – similar to how it’s done when installing software or purchasing digital products.

Let’s look at some more real-world examples, because they help us understand things best.

Digital Products:

Streaming services (Netflix, Spotify):

These platforms often use autoplay as a default. For example, Netflix automatically plays the next episode in a series unless the user opts out. This default setting keeps users engaged and watching longer.

Email subscriptions:

Many apps and websites default users into receiving newsletters or promotional emails unless they opt out. This increases the likelihood that users stay subscribed and engaged with the content.

Software updates (operating systems and apps):

Operating systems like Windows and macOS, as well as various apps, often have automatic updates set as the default. Users who don’t change this setting get the latest features and security patches without having to actively manage updates.

Privacy settings (social media):

Social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram often have default sharing settings that dictate who can view your posts or profile information. Many users stick with these default settings, impacting their privacy and social interactions.

Cloud storage:

Automatic backup: Services like Google Drive, Dropbox, and iCloud offer default settings for automatic backup of photos, documents, and other files. This ensures that users’ data is regularly backed up without the need for manual intervention.

Physical Products:

Energy-efficient appliances:

Modern refrigerators and washing machines often come with default eco-settings. Users who don’t change these settings consume less energy, benefiting both the environment and their energy bills.

Smart thermostats:

Pre-set temperature schedules: Smart thermostats, like those from Nest, come with pre-set temperature schedules designed to optimize energy usage based on common household routines. Users who don’t modify these settings still enjoy energy savings.

Healthcare and medication:

Automatic prescription refills: Some pharmacies offer automatic prescription refills as a default service. This ensures that patients receive their medication regularly without needing to remember to reorder.

Hybrid and electric vehicles:

Eco driving mode: Many hybrid and electric vehicles come with an eco driving mode as the default setting. This mode helps maximize fuel efficiency and reduce emissions without drivers having to make conscious adjustments.

Grocery delivery services:

Default substitutions: Services like Amazon Fresh or Instacart often default to allowing substitutions if an item is out of stock. This means customers automatically receive similar products without needing to approve each substitution.

These examples illustrate how the default effect can be used to promote user-friendly and environmentally friendly behaviors, making user experiences smoother and more intuitive.

So, take a moment and think – how can you apply this in your own work?

b) Work With Friction (Pracujte S Trením)

Working with friction and creating the path of least resistance is something all product architects, designers, or anyone crafting customer journeys know all too well. If you want to change customer behavior, you must ensure that the desired action is as easy as possible. Reduce obstacles and reshape the environment to make decision-making easier.

What are common causes of friction?

In other words, what makes decisions harder and the entire process more challenging?

Decision-making difficulty

When dealing with complex products or customer journeys, a great exercise is to count how many decisions a person must make, and what types of decisions, to reach the final goal.

For example, if you have AI software for generating images, examine every point where the user has to make a decision, starting from clicking the ad to the moment they generate and save an image they’re satisfied with.

The perception of high effort

We’ll discuss this in more depth in the next section, but in short, when the process feels overwhelming or too difficult, people often abandon the task altogether.

Choice overload

Offering too many options at the start can overwhelm customers, whether it’s a variety of services, products, or even too many stimuli on a single page. Even when you offer just one product, there can be too many distractions on the page.

Here’s an example:

On this page, the customer is bombarded with many stimuli and potential decisions to make, even though they’re really only looking for one service. Each extra clickable element adds to the complexity, making the journey more cumbersome.

Every extra step

Similar to counting decisions, it’s important to track every single step in the customer journey. This includes everything — every click, every form, every piece of information requested adds friction.

Uncertainty

If a person feels unsure or confused, they often eliminate that uncertainty by avoiding change altogether. When does this tendency arise?

Dilemma: Multiple equally appealing choices can cause hesitation.

Stress: High-pressure situations can make decision-making harder.

Confusion: Lack of clarity leads to inaction.

Netflix, for example, anticipates and resolves key customer concerns even before they arise. They reduce uncertainty by making the experience as seamless as possible.

Similarly, an e-commerce business might offer product-specific protection or warranties during checkout. One store, for example, offered a “first setup service” for new computers, which was so compelling that three members of my family decided to purchase from them specifically because of this offer.

My tip: Identify potential concerns your customers might have and address them before they even realize they have those concerns.

It’s not easy, but it’s far from impossible.

c) Perceived Effort

The effort people actually put in and the effort they think they will need to put in can differ greatly.

The key is to make sure the customer or client feels that the required behavior is easy to carry out. “Feel” and “perceive” are the crucial words here because perceived effort ≠(not equal) actual effort. Often, it looks like this:

If you show a customer a long form like this, they’re likely to have no interest in filling it out:

But if you break it down into a few smaller steps, suddenly it doesn’t seem as bad:

What are the most common reasons that cause confusion and a sense of greater effort in people?

Unstructured communication and unclear instructions

Using complicated language or a lot of foreign terms without explanations

Vague and overly complex information

Poorly presented data

Here are some quick examples of how you can change a sentence to have a dramatically different impact:

Before: “Please fill out this form to be registered.”

After: “Just 3 easy steps, and you’re registered!”

or

Before: “Hello, can I speak with you? I need some help.”

After: “Hi, I won’t take much of your time—just have two quick questions for you.”

Small adjustments like these can significantly reduce the perceived effort, making tasks feel more manageable for customers and clients.

2) Indirect Communication

The title of this section has been adapted from the original, expanded with new subsections. The goal here is to teach how to create things that communicate effectively with the right person in the right way.

By communication, I mean how you present information, and it is indirect because this information doesn’t hold primary importance but instead supports or amplifies the effect of the initial interventions.

Let’s take a look at some ways to implement this effectively.

a) Implement Intentions

Implementation Intentions are a powerful strategy to turn goals into actions by pre-planning specific steps and reactions to potential obstacles.

This approach involves creating “if-then” plans that clearly outline when, where, and how you will act to achieve your goal. By specifying the conditions under which you will take action, you create these implementation intentions, which help automate behavior and increase the likelihood that you’ll follow through on your plans—even in the face of distractions or challenges.

This method has proven highly effective in achieving goals in various fields, from health and fitness to productivity and education.

Real-world examples:

Digital Products

Fitness Apps (e.g., MyFitnessPal, Fitbit): These apps allow users to set specific goals like, “If it’s Monday, Wednesday, and Friday at 7:00 AM, then I’ll go for a 30-minute run.” The apps send reminders and track progress, helping users stick to their workout plans.

Task Management Apps (e.g., Todoist, Trello): Users can create specific tasks with deadlines and reminders, like “If it’s 9:00 AM on weekdays, then I’ll spend 10 minutes reviewing my to-do list.” These apps encourage users to check off and complete their tasks, reinforcing productive habits.

Physical Products:

Meal Prep Containers: For people who want to eat healthier, using meal prep containers can support implementation intentions like “If it’s Sunday afternoon, then I’ll prepare and portion out my meals for the entire week.” This preparation helps ensure that healthier options are readily available.

Reusable Water Bottles: To increase water intake, someone could use a reusable water bottle with time markers, setting an intention like “If it’s 8:00 AM, then I’ll fill my bottle and drink it by 10:00 AM.” The time markers serve as visual reminders to stay hydrated throughout the day.

b) Feedback

This section is one of my favorites and by far one of the most important. It has taught me to think differently and to create great products, services, and applications.

In my opinion, this way of thinking shouldn’t be limited to behavioral interventions alone.

I use it by asking, for every product I work on—especially those meant for people—what kind of feedback it will provide and how that feedback will be communicated.

The best way to help people improve their performance is by giving them effective feedback. Well-designed systems clearly inform users when they are doing something right and when they are making mistakes.

Let’s look at a few examples:

In my case study on Alza’s e-commerce, I demonstrated how, through design or UX/UI, we can significantly influence the customer experience by highlighting users’ errors in real time, showing exactly what mistakes they made:

Fitness Apps (e.g., MyFitnessPal, Strava): These apps provide users with detailed feedback on their workouts, including metrics like distance, pace, calories burned, and progress over time. This feedback helps users stay motivated, identify areas for improvement, and track their fitness goals.

Language Learning Apps (e.g., Duolingo, Babbel): These apps offer instant feedback on exercises and quizzes, correcting mistakes and providing explanations. This immediate feedback helps learners understand their errors, improve their language skills, and stay motivated to continue learning.

Let’s also consider some real-world examples:

Cameras: When taking a picture, you first press the shutter button lightly to focus. Then, pressing harder triggers the actual capture, often accompanied by a slight click or a brief blackout in the viewfinder. One company tried to remove these features for smoother use but faced backlash from users, who complained and stopped buying their cameras.

Wall Paint: A longstanding issue with white paint has been the difficulty in seeing where it’s already been applied, often leading to visible layers. One innovative company introduced a white paint that initially appeared slightly yellow when applied but faded to white after a few minutes. This paint became hugely popular.

Induction Cooktops: Even after being turned off, these cooktops display an “H” to indicate that the surface is still hot.

Wearable Fitness Trackers: Devices like the Apple Watch or Garmin Fitness Trackers offer real-time feedback on physical activity, heart rate, and sleep patterns.

A key type of feedback is the warning that “things have gone wrong” or, even more usefully, that “things are about to go wrong.”

Computers warning of low battery

Cars displaying warning lights

Blood tests that reveal problems before they become serious—this is why regular check-ups are important!

However, as with everything, there’s a downside to feedback.

If you’re designing warning systems, avoid falling into the trap of “the boy who cried wolf.”

The Aesop’s fable tells the story of a boy who repeatedly cried “Wolf!” falsely, causing the villagers to stop responding to his calls. When a real wolf came, no one believed him, and the wolf attacked his flock.

One moral of the story is that lying leads to a loss of trust, but another lesson is relevant for us: you can’t give so many warning signals that people start ignoring them!

Here are some examples:

Antivirus Software: Constant pop-up alerts about security threats or updates can lead users to ignore these warnings, potentially compromising the safety of their device.

Cars: Modern vehicles may have various alerts, like persistent beeping when the seatbelt isn’t fastened or warnings about low tire pressure. If these alerts happen too often or without reason, drivers may start ignoring them.

Smartphones: Continuous notifications from apps, social media, and emails can cause “notification blindness,” where users stop paying attention or responding to important alerts.

Computer Programs: Applications or operating systems that constantly remind users about updates or trivial messages may lead to users ignoring all notifications, potentially missing critical updates.

Healthcare Devices: Wearable health devices that constantly track and alert users about various metrics (e.g., heart rate, blood oxygen levels) may overwhelm users, causing them to ignore important warnings.

If you think carefully about this method or insight, you can create products that are far superior to the competition.

c) Psychology of Waiting

The psychology of waiting is something we don’t often think about, despite its significant importance. After all, there’s almost always a situation where we have to wait for something.

What can you do to keep people satisfied with your services, even when they have to wait longer than expected?

Here are some examples from the digital world:

Budget flight service Pelikán displays a progress graphic while searching for flights. This visual shows users what’s happening behind the scenes and how much effort is involved in finding the best deals.

Loading screens (e.g., Google, YouTube): These platforms use progress indicators during loading times. For instance, YouTube displays a spinning wheel or progress bar, helping manage user expectations and reducing the anxiety of waiting.

Food delivery apps (e.g., Uber Eats, DoorDash): These apps provide real-time updates on the status of your food delivery, including estimated delivery times and the current location of the driver. This transparency reduces uncertainty and keeps users informed and engaged.

Revolut implemented a small but effective intervention by showing the steps happening during international money transfers. It’s a simple touch, but it had a profoundly positive impact on me.

A new modern twist on this method was also used by OpenAI in its ChatGPT service. Instead of a loading bar, the text being generated gradually appears as if it’s being typed out. This subtle yet effective design is now being implemented in various text generation tools.

Examples from the physical world:

Streetpong at traffic lights: In some countries, pedestrian crossings have installed devices for playing pong while waiting at long traffic lights. People enjoy it, often smiling, making new connections, and some visitors come just to play.

Airports: Many airports purposely place baggage claim areas far from gates to reduce the perceived wait time for luggage.

Theme park queues (e.g., Disney World, Universal Studios): These parks use interactive elements, like videos and themed decor, to make waiting more enjoyable. They also provide estimated wait times to manage visitor expectations.

Call centers and bank lines: Many call centers and banks inform customers of their position in line and the estimated waiting time. Some even offer a callback option, reducing the frustration of being on hold.

These examples show how understanding the psychology of waiting can lead to better user experiences by keeping users informed, engaged, and satisfied during delays.

Here are 8 key factors that make waiting feel longer:

Unoccupied time feels longer than occupied time: If you have something to distract you, time passes faster. Some hotels even place mirrors in elevators because people like to look at themselves.

People want to get started: That’s why restaurants often hand out menus while you wait for a table.

Anxiety makes waiting feel longer: If you think you’ve chosen the slowest line at the grocery store, or you’re worried about missing a flight, waiting feels even longer.

Uncertain waits feel longer than known waits: People are calmer when told, “You’ll see the doctor in 30 minutes” compared to “The doctor will see you shortly.”

Unexplained waits are longer than explained waits: We’re more patient waiting for pizza during a storm than when it’s clear outside.

Unfair waits feel longer than fair waits: People want fairness in waiting. For instance, there’s tension when waiting on a crowded subway platform, unsure who will get on the train first.

The more valuable the service, the longer people are willing to wait: You’ll wait longer to see a doctor than a salesperson, and longer in line for an iPhone than for a toothbrush.

Solo waiting feels longer than group waiting: When people chat with each other, they become less aware of the wait.

So, don’t make people wait. But if they must, make the wait as pleasant as possible.

d) Operational Transparency

I really like using this method, and it’s one of my favorites.

Operational transparency involves openly sharing information about the processes and efforts behind a service or product, which can significantly increase user commitment and trust.

By making behind-the-scenes activities visible, organizations can build credibility, reduce uncertainty, and boost user engagement.

Transparency helps customers appreciate the work involved and fosters a sense of involvement and trust. This can motivate users to remain loyal to the service or product as informed and valued participants in the process.

Here are some examples from the everyday world:

Digital Products

Uber was the first service to impress me with this technique when they introduced the visualization of drivers in the app. This feature shifted my preferences so drastically that I exclusively switched to Uber and never used a traditional taxi service again.

Domino’s Pizza also jumped on this trend when they began showing the various stages of pizza preparation, including the current status of your order. This feature allows you to track the entire process, from dough preparation to delivery, which enhances satisfaction and reduces uncertainty while waiting.

Amazon Order Tracking: Amazon provides detailed order tracking information, showing every step of the delivery process from the warehouse to the customer’s doorstep. This operational transparency reassures customers that their orders are safe and efficiently handled, keeping them engaged throughout the waiting period.

Spotify Wrapped: Spotify offers an annual summary called “Spotify Wrapped,” providing users with an overview of their listening habits over the past year. By transparently sharing music consumption data, Spotify boosts user engagement and satisfaction, encouraging them to keep using the platform.

Physical Products

Tesla frequently shares updates on its manufacturing processes, including videos and insights about their Gigafactories. This transparency builds trust with customers by showcasing the complexity and effort involved in producing their electric vehicles, fostering loyalty and enthusiasm among Tesla owners and fans.

Open Kitchens in Modern Restaurants: Many modern restaurants have adopted the concept of open kitchens, where guests can watch chefs prepare their meals. This operational transparency enhances the dining experience by displaying the skill and care put into meal preparation, increasing customer appreciation and satisfaction.

This technique is quite similar to the previous one, psychology of waiting and the two often overlap in many cases.

That wraps up this section—let’s move on to the final one!

3) Create Social Expectations

Not only do you know this method, but I’ve also mentioned it several times. We are social creatures, and the principles of social proof can be used in various ways, which we’ll break down now.

One example I heard during a workshop in Denmark is one I not only regularly apply in my life but also used during a serious accident in the U.S.

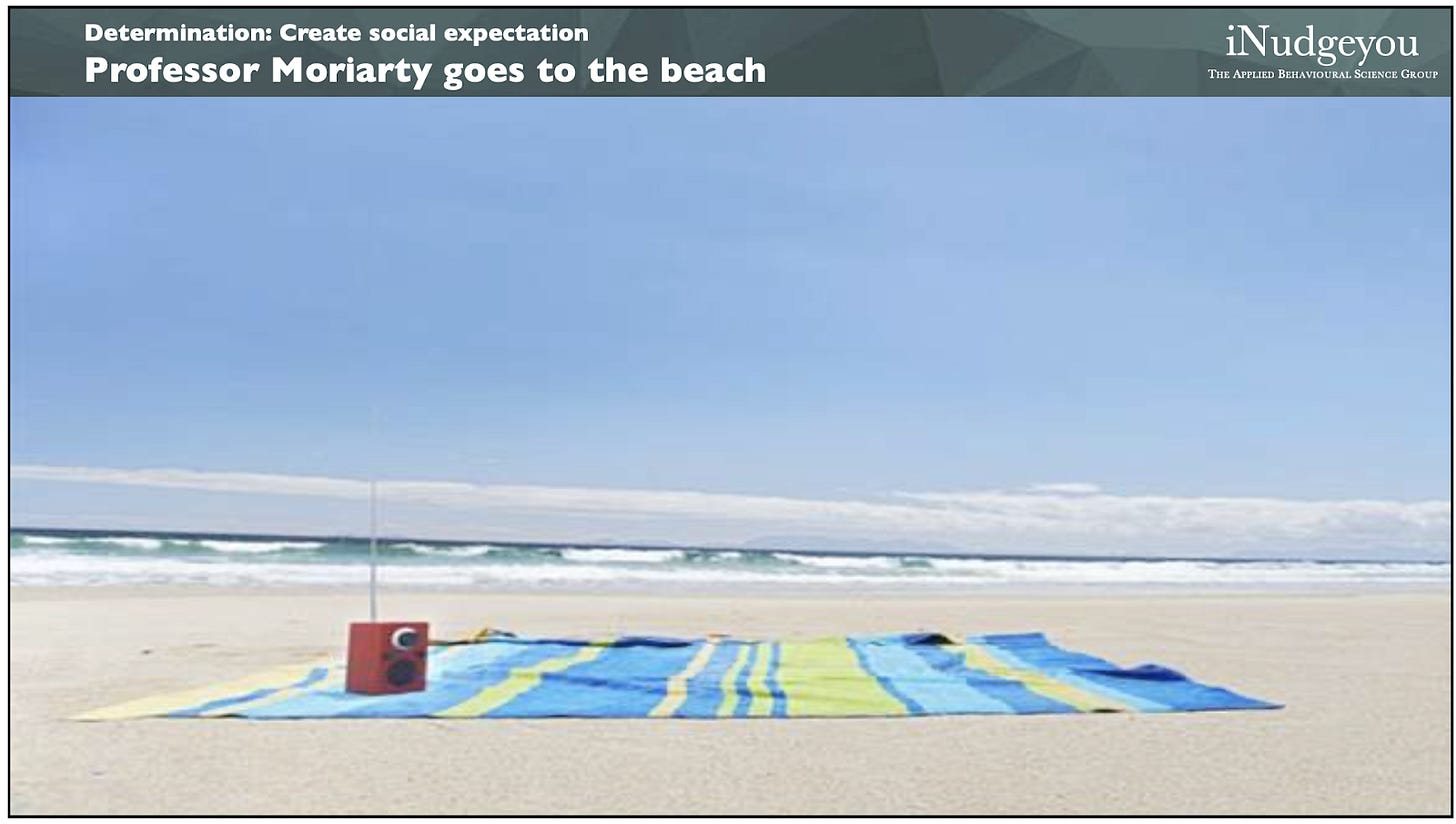

The name of this research is “Professor Moriarty Goes to the Beach,” and as you might have guessed, it was conducted by Professor Moriarty himself.

Moriarty conducted an experiment on a crowded beach. He laid out his belongings and stayed there for a while. The essence of the experiment was that Moriarty would leave his blanket for a while, at which point a “thief” (who was in on the experiment) would come and steal his things, then run away.

The experiment had two different setups:

Control Group: Moriarty didn’t say anything and just left.

Implementation Group: Moriarty asked people nearby to watch his things while he was gone.

The goal was to measure how many people from each group would run after the thief, and here are the results:

The goal was to measure how many people from each group would run after the thief, and here are the results:

In the control group, where Moriarty said nothing, only 20% of people chased the thief.

In the implementation group, where Moriarty specifically asked for help, 95% of people ran after the thief.

This simple request created a sense of social responsibility. Once people were directly asked, they felt accountable. Without that direct request, most people assumed that it wasn’t their problem.

There are many real-life examples of this phenomenon. In one well-known case, a woman was beaten to death on a street in broad daylight. Even though she screamed for help, no one called the authorities because everyone assumed someone else would take action. This is known as the bystander effect, which later became a significant subject of psychological study.

The same can happen in professional settings. If tasks and responsibilities are not clearly assigned to individuals, nothing gets done properly because everyone assumes someone else will handle it.

When I was studying in the U.S., I had a car accident. I was in a car with a close friend, and as we were turning onto the main street, another car ran a red light and crashed into us. Glass was everywhere, my friend was hysterically screaming, and people around us were just standing, staring, and taking photos. Only when I began shouting at specific people, telling them what to do and who to call, did everyone spring into action and help.

I still find it remarkable how such a simple act of assigning responsibility was so incredibly effective. It’s even more powerful when you assign tasks in front of others, as it creates social pressure and accountability.

This section got a bit lengthy, so let’s dive into more specific techniques you can use in practice.

a) Create Commitments

Creating Commitments is a powerful strategy to enhance dedication and foster behavioral change. When people make commitments, especially in public or social contexts, they are much more likely to follow through. This stems from their desire to remain consistent with their promises and maintain a positive self-image.

Commitments act as a strong motivational force, helping us stay the course on our goals, even when challenges arise. Encouraging a sense of responsibility and accountability significantly increases the likelihood of achieving desired outcomes.

Here are some real-life examples:

Digital Products:

We’ve already touched on some digital products, but now we’ll look at them from a slightly different angle:

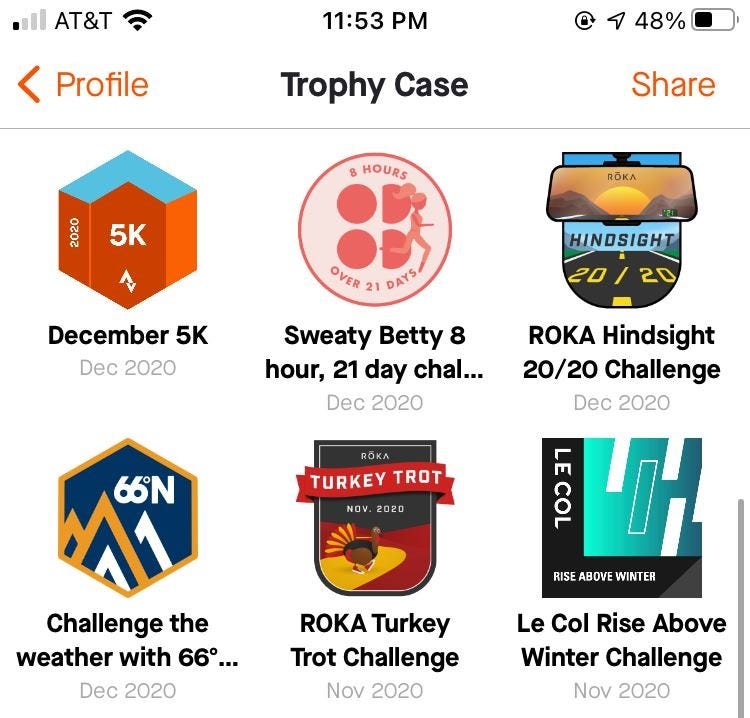

Fitness Apps (e.g., Strava, Fitbit Challenges):

These apps encourage users to set fitness goals and participate in challenges with friends or community members. Publicly committing to these goals and sharing progress with others increases accountability and motivation to stick with workout routines.

Goal-Setting Apps (e.g., Habitica, StickK):

Habitica turns goal-setting into a game where users commit to tasks and earn rewards for completing them.

StickK allows users to create commitment contracts with financial stakes, where users pledge to donate money to a cause they dislike if they fail to meet their goals. These mechanisms increase commitment by adding social and financial accountability.

Physical Products:

Reusable Shopping Bags:

Many grocery stores offer discounts or rewards to customers who bring their own reusable bags. By committing to this eco-friendly practice, customers are more likely to consistently remember and use their bags, reinforcing sustainable habits.

Subscription Services (e.g., Meal Kits like HelloFresh, Blue Apron):

These services require users to commit to regular meal deliveries. This commitment motivates users to prepare and consume healthier, home-cooked meals, promoting better eating habits while also helping reduce food waste.

These examples demonstrate how creating commitments can effectively support goal achievement by fostering accountability and increasing motivation—whether in digital or physical contexts.

b) Leverage Social Norms

Leveraging Social Norms is a powerful way to influence commitment and guide behavioral change. Social norms are unwritten rules that dictate acceptable behavior within a group or society. By highlighting these norms, individuals can be encouraged to adopt positive behaviors and feel a sense of belonging and approval.

When people see others engaging in a particular behavior, they are more likely to adopt it themselves. This can be especially effective in promoting healthy habits, environmentally friendly actions, or any behavior that benefits individuals and society. Using social norms can create a collective momentum that reinforces the desired behavior.

Here are some examples from the digital and physical worlds:

Digital Products:

Social Media Platforms (e.g., Facebook, Instagram):

These platforms leverage social norms to encourage engagement by showing users what their friends and peers are liking, sharing, and commenting on. Seeing friends engage with certain content can motivate people to interact with similar content, increasing participation and adherence to community standards.

Energy-Saving Apps (e.g., Opower):

Opower partners with utility companies to provide reports to customers comparing their energy usage to that of their neighbors. By showing users that their neighbors are using less energy, the app uses social norms to encourage people to reduce their own consumption, promoting more energy-efficient behavior.

Physical Products:

Towel Reuse Programs in Hotels:

Many hotels place signs in bathrooms stating that most guests reuse their towels. These messages use social norms to encourage new guests to do the same, promoting environmentally friendly behavior and reducing water and detergent consumption.

Recycling Bins in Public Spaces:

Placing recycling bins in prominent locations with clear signs about how many people in the area recycle taps into social norms. When individuals see that many others are recycling, they are more likely to participate in recycling efforts themselves.

By utilizing social norms, businesses and organizations can influence commitment and behavior change, motivating individuals to adopt positive behaviors that align with societal expectations and collective actions.

Conclusion on Commitment: Understanding How Motivation Works

As we wrap up this section on commitment, it’s essential to touch on motivation—the driving force behind commitment. While knowing how to foster commitment is crucial, often commitment is powered by the ability to motivate others or ourselves.

This brings us to an essential quote:

“If you would persuade, appeal to interest and not to reason.” — Ben Franklin.

There is a fantastic book titled “Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us” by Daniel H. Pink, which dives deep into the subject. From that book, I’ve gathered key insights that I believe are important to share here.

Pink divides motivation into three categories:

Motivation 1.0: This is basic survival motivation—our need to fulfill primal urges like hunger, safety, and reproduction. It was dominant in the earliest stages of human evolution.

Motivation 2.0: This type of motivation is based on rewards and punishments. For most of human history, society relied on extrinsic motivators to drive behavior—such as bonuses for high performance or penalties for poor performance. However, this carrot-and-stick model doesn’t always work for more complex tasks.

Motivation 3.0: This is built on the Self-Determination Theory (SDT), which states that humans have an innate desire to be autonomous, self-directed, and connected to others. To truly unlock this motivation, you need to create environments that allow people to experience autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

The key elements of Motivation 3.0 are:

Autonomy: The need to direct our own lives and have the freedom to make decisions.

Mastery: The urge to get better at something that matters and to continually improve.

Purpose: The need to feel that what we are doing is meaningful and contributes to something greater than ourselves.

Breaking down all of these areas in depth would require an entire book, so for those truly interested in understanding motivation, I highly recommend reading “Drive”. But these are the fundamental elements to keep in mind when trying to motivate yourself or others effectively.

If the way I approach things resonates — or if your product, idea, or strategy feels even slightly “off” — I might be able to help.

Let’s have a quick 20-minute call to find clarity together:

Final Thoughts

This concludes not only the section on commitment but the entire ABCD model we’ve explored in this article. By now, you should have a much better understanding of what influences human behavior, how to interpret it, and how to design interventions that resonate with people at a deep level.

And as promised, in the next article, I’d like to showcase an exceptional campaign that not only succeeded in influencing behavior but also brilliantly linked a campaign for a good cause with product execution. This connection truly contributed to changing behavior—a rare example where such success wasn’t just PR for a major company or a marketing budget spend, but a real case of impactful behavioral change.

I hope this journey through behavior, decision-making, and motivation has provided valuable insights, leaving you better equipped to understand and influence human behavior in your projects and ventures.

- Peter

For those of you who want to explore the previous sections:

[1/6] Introduction to the ABCD Framework

For those who would like to support this effort, you can find the entire study here for a symbolic price. It also includes examples and exercises that you won’t find in the article.